|

| Courtesy of the Waring Historical Library, MUSC, Charleston, S.C. http://waring.library.musc.edu |

|

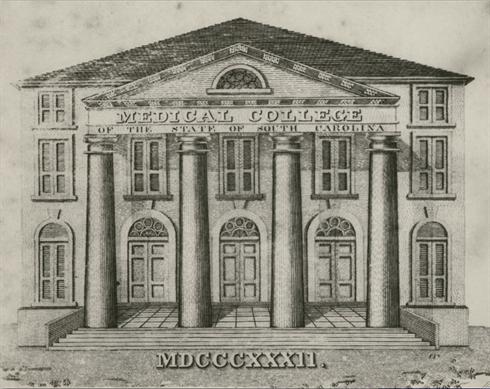

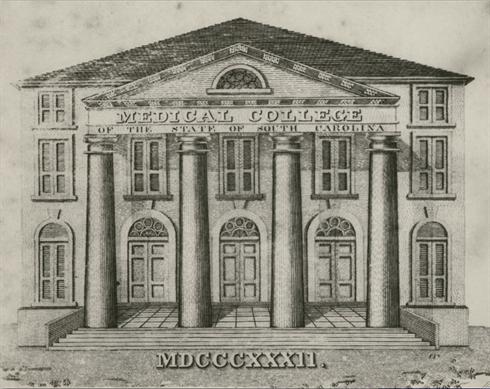

"Medical College of the State of South Carolina," 1832. |

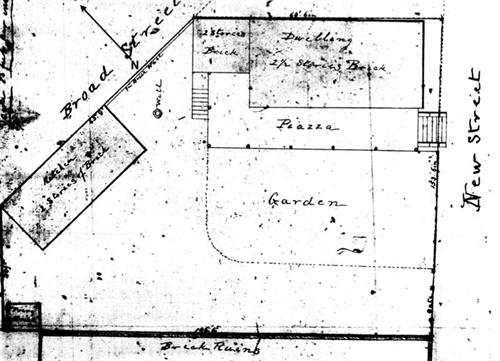

In 1792, Thomas Wade West and John Bignall, managers of the Virginia Company of Comedians, announced plans for a new theater in Charleston. Designed by James Hoban (best known as the architect of the White House in Washington), the masonry playhouse was built by contractor Capt. Anthony Toomer. On August 14, 1792, the City Gazette reported "the ground was laid off for the new theatre, on Savage's Green. …125 feet in length, the width 56 feet, the height 37 feet, with a handsome pediment, stone ornaments, a large flight of stone steps, and a courtyard palisaded. The front will be on Broad Street, and the pit entrance on Middleton Street [New Street]."

West and Bignall's 1,200-seat theater opened in February 1793, midway through the social season, presenting dramas that included both dancing and music by actors and musicians recruited from northern cities. Because the players in the thirteen-piece orchestra also served the St. Cecilia Society, the schedules of that concert series and the theatre were carefully coordinated. Most of the performers, fearing Charleston's deadly fevers, moved north again before summer.

In November, 1793, the City Gazette reported that the theater had been upgraded in anticipation of a new season, and that a "number of capital performers" from England had arrived in Virginia aboard the ships Union and Eliza. Among them were Mr. and Mrs. Edgar; Mr. Clifford, the "celebrated singer from Vauxhall;" Mr. and Mrs. Henderson, late of the Liverpool theatre; Mr. T. West from the Bath theatre; and the "three Mr. Sullys" [Matthew, Lawrence, and Thomas]. This illustrious company joined the previous year's returning performers. On opening night, January 15, 1794, they presented a double bill: "The Tragedy of the Earl of Essex" and a comic opera "The Farmer, or The World's Ups and Downs."

Winter for well-off Charlestonians included a busy round of theatre, musical concerts, and subscription balls. Soon after the Broad Street Theatre opened, Santo Domingan refugee John Sollée built a French-language theater on Church Street [a lot that was later incorporated into the Charleston Cotton Press operation, then redeveloped as today's 93 Church Street]. The French Theatre's inaugural performance, April 21, 1794, featured a comedy, "Harlequin Robbed," singing, and tightrope dancing, all starring Alexander Placide and his so-called wife, Suzanne Théodore Vaillande. Competition between the two theaters was fierce, and heightened by conflicting political alliances after France declared war on Great Britain in February 1793. While the wealthy elite patronized Shakespearian productions on Broad Street, supporters of the Jacobin revolutionaries flocked to the comedies, acrobatics, and light opera presented at the French Theater.

West and Bignall's Charleston Theater was effectively out of business at the end of the 1795-96 season. The two companies, French and English, merged during the spring, offering several benefit performances, with proceeds going to the various performers or to charitable causes such as "the orphans of Charleston." Through the summer of 1796, the merged company kept the Church Street theater open under the name of "City Theatre," while the Broad Street house remained dark.

Beginning in 1799, performers who stayed in Charleston through the summer, and those who had made the city their permanent residence, found employment at Alexander Placide's Vauxhall Gardens. Finally, in the spring of 1800, the parties cooperated to open both playhouses, the Broad Street venue presenting drama and Church Street for music, acrobatics, and ballet. Sollée then renovated his Church Street property as a music hall and ballroom, known for years as "Concert Hall." After 1800, the Broad Street theater was Charleston's only playhouse, and generally referred to as The Theatre.

The theater closed when the War of 1812 broke out, reopening in the autumn of 1815 under the management of English actor Joseph Holman. He planned a network of southeastern theaters with a large company rotating among such cities as Norfolk, Augusta, and Savannah. Upon Holman's death in 1817, his son-in-law Charles Gilfert took over. During Gilfert's tenure, President James Monroe visited Charleston's theater in 1819, and Junius Brutus Booth performed two engagements in the winter of 1821-22. Members of the company, including Mrs. Gilfert, played supporting roles to Booth's Richard III, Hamlet, and Lear. Charles Gilfert was a well-regarded musician and composer, but he failed as a manager. Debts and lawsuits forced him to lose his lease on the theater, and he was briefly jailed.

Gilfert's successor, Mr. Cowell, "formerly of the Theatre Royale, Drury Lane," reopened the theatre in February 1826, promising new scenery and splendid pageants. (He also brought the New-York and Philadelphia Company of Equestrians and its twenty horses to Charleston. They performed at the old circus facility in the back of Vauxhall Garden.) Regardless of her husband's financial problems, Mrs. Gilfert was a local favorite, and soon after Cowell assumed management, he handled a benefit performance for her. As an inducement to attendance, on February 20, 1826, the City Gazette advised its readers that the "New Portico (a plan of which may be seen at the Box Office in Broad Street), which is to be completed before the opening of the Theatre at the next season, is by agreement from the Directors to be erected at the sole expense of Mrs. Gilfert." Within a few years, the portico had been added to the Broad Street façade.

Theater manager Cowell presented extravagant entertainments. In early March, 1826, the circus horses appeared on stage during the "grand drama of the Cataract of the Ganges." Between March 13 and April 11, 1826, Edmund Kean, Junius Booth's great rival in the Shakespearian world, played King Lear, Othello, and Richard III.

Annually, theatrical entrepreneurs arrived in Charleston, spruced up the theater, and put their companies to work. Yet by 1832, attendance had fallen off sharply. The Southern Patriot attributed the decline to the steep price of tickets at a time when many had "circumscribed means." The tight wallets were a response to Charleston's weak economy, and the theater soon closed permanently. On July 25, 1833, readers of the Southern Patriot saw a small notice: "The building at the west end of Broad Street, called the Charleston Theatre, has been purchased by the faculty of the Medical College of the State of South Carolina for the sum of $12,000. It will be fitted up for the classes attached to this institution."

The Medical College of South Carolina had opened in 1824, financed by its faculty of medical professionals. By 1832 the college, located at the corner of Franklin and Queen streets, was being directed by the Medical Society of South Carolina. A rift developed between management and faculty of the Medical College, and the faculty organized an independent institution, The Medical College of the State of South Carolina. With an enrollment of 105, the new college opened in 1833 in the Broad Street theater. The Medical Society struggled to recruit faculty and students to the original college, but within a few years gave up the effort. In 1838 the Medical College of South Carolina closed, transferring its property to the Medical College of the State of South Carolina. The theater was no longer required for classrooms, and in 1840 the faculty opened it as a teaching hospital. College Hospital accepted both white and black patients, and "those laboring under madness in its various forms," as well as maintaining an obstetrics ward. The institution was eventually supplanted by Roper Hospital. Butler, Nicholas Michael. Votaries of Apollo. The St. Cecilia Society and the Patronage of Concert Music in Charleston, South Carolina, 1766-1820. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007.

"Footlight Players Present 16th Season." The Charlestonian, Charleston Chamber of Commerce, November 1947.

Ravenel, Beatrice St. Julien. Architects of Charleston. Charleston: Carolina Art Association, 1945. Rev. 2nd ed., 1964.

Waring, Joseph Ioor. A History of Medicine in South Carolina, 1825-1900. Columbia: South Carolina Medical Association, 1967. Charleston City Gazette. November 23, 1793; January 27, 1826; "French Theatre." April 18, 1794.

South-Carolina State Gazette, January 11, 1794.

|

37NewStreetToLoad_500x500.jpg)