| 16. Armory (1750), Watch House (1767), Guard House (1838-1886) |

|

||

The Guard House after the 1886 earthquake. |

In colonial Charles Town, public safety and law enforcement were managed by the Town Watch, a paramilitary unit. After the City of Charleston was incorporated in 1783, the City Guard took over the function and buildings of the Town Watch. The City Guard became a uniformed police force in 1856. The various organizations were all housed at the southwest corner of Broad and Meeting streets from 1769 until 1886.

The Watch House or Guard House was a police station, with rooms for offices, meetings, and drills, and a barracks for the guards. By 1711, there was a Watch House in the building above the Half Moon Battery. In 1767 the Commons House of Assembly granted an appropriation to build a new Watch House, and to build a waterfront Exchange and Custom House above the Half Moon Battery. The Act of Appropriation stipulated that "A convenient, proper, and handsome Watch House is first to be built in Broad Street, between the Public Armory, State House, St. Michael's Church, and the Market. When that is completed, the old Watch House is to be pulled down and the Exchange and Custom House erected in its stead."

The new Watch House, constructed by William Rigby Naylor and James Brown, was complete by 1769. The size of the force grew along with Charleston’s population, and the buildings were altered and remodeled several times. In early 1838, City Council determined that Charleston’s 160-man guard required an entirely new building. They needed large halls roomy enough to use for drills, a court room and detention area, and quarters for the men.

The new Guard House was designed by architect Charles F. Reichardt, whose other monumental buildings (Charleston Hotel and New Theatre) were part of Meeting Street's transformation into a grand urban thoroughfare. Reichardt's plan featured two prominent elevations, a colonnade along Meeting Street (which was removed in 1856), and a portico facing Broad Street.

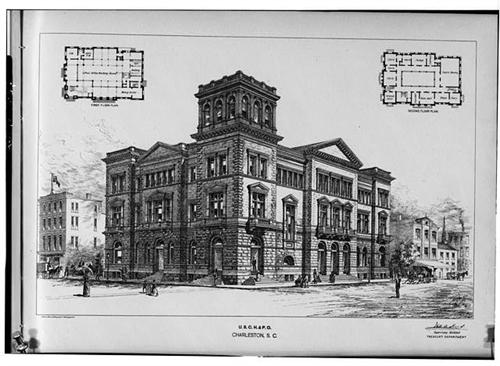

The 1838 Guard House was wrecked by the earthquake of August 1886, its upper façade crashing through the portico into Broad Street. The building was deemed unsalvageable, and its remnants were gradually cleared from the site. In its place rose the present United States Courthouse and Post Office, completed in 1897.

The only remaining element of the Guard House is said never to have been installed there. The fine double-leaf gate crafted by ironworker Christopher Werner, and perhaps designed by Reichardt, was rejected as too expensive. In 1849, George A. Hopley acquired the wrought-iron gate and installed it at the garden entry to his residence at 32 Legare Street. The grand Sword Gate, with its swords and spears, gave its name to the house.

The 1887 Police Station

After the 1886 earthquake ruined the police station, the department temporarily moved its headquarters to the gymnasium of Charleston High School (Meeting and George streets). In April 1887, the city leased Hibernian Hall to use as a police station for six months. After selling the Broad Street site to the federal government, the city issued an invitation for bids to build a new Central Police Station at the corner of King and Hutson streets, a lot which was "long vacant, neglected, and most unsightly."

Beginning in June, the work progressed quickly and the police station formally opened on February 7, 1888. There were offices and hearing rooms, sleeping quarters for officers, an armory, ten cells, and stables for nine horses. The News and Courier considered the new building “an ornament even by contrast with such prominent competitors as the Citadel Academy, St. Matthew’s Church, the Citadel Square Baptist Church, and the Orphan House.”

The location of the Central Police Station adjacent to The Citadel, South Carolina’s military college, became an issue during the early twentieth century. Not only did late-night activity disturb the cadets, but the jail’s cellblock abutted The Citadel’s officers’ quarters. The Citadel was already interested in expanding its campus, so the South Carolina Military Academy asked the City of Charleston to sell the police station.

City Council was agreeable, and, without even knowing where a new police station might be built, offered to sell the Station House to the State of South Carolina at a very favorable price. State legislators inspected the police station, found it in good condition, and the agreement was finalized in February 1906. The Citadel used the building until 1922 when the campus was relocated to its present site between the Ashley River and Hampton Park.

The 1908 Police Station

The 1906 agreement between the City of Charleston and the State of South Carolina for the sale of the Central Police Station allowed the city more than a year to turn over the building. During that time, City Council would select and purchase a site, and construct a new main station house. The first suggestion, that the city’s Thomson Auditorium could be reworked or replaced to accommodate the police station and jail, set off a torrent of protests from property owners in the residential neighborhood of Harleston Village.

After several months of quiet negotiations, in May 1906, City Council chose a site at the corner of St. Philip and Vanderhorst streets. J. H. Devereux, Jr., sold the lot with a building known as Devereux’s Tenement to the city. Council’s Committee on Public Safety had already sent requests to police departments nationwide for information about planning and design trends, and had received from New York City “a plan of a model police station which is particularly favored, as it embraces all the latest features of police station construction.”

City Council requested architectural proposals from A. W. Todd and J. D. Newcomer of Charleston, and several out-of-town firms experienced with police stations and prisons. The architect selected was R. Thomas Short of New York, whose plan was “most admirably arranged.”

By the 1960s, Charleston’s 1908 police station was considered obsolete. Maintenance had been neglected, and the ceilings were thought to be too high for efficient climate control. A bond referendum to fund a new police department headquarters passed in 1968. In January 1974, the Charleston Police Department moved into a new complex at Lockwood Drive Extension. Demolition of the old police station began in November, 1974.

“The Palace of the Police.” News and Courier, January 22, 1888.

“The Police Station Site.” Charleston Evening Post, February 23, 1906.

“Police Station Plans.” Charleston Evening Post, June 11, 1906.

“Plans for Police Station.” News and Courier, November 2, 1906.

“Police Station Lacks Little Now. $70,000 building will be entirely finished by Thursday.” Charleston Evening Post, January 21, 1908.

“New Police Station Accepted. Committee of Public Safety Receives the Building.” News and Courier, January 30, 1908.

“City Police Station Dilapidated Eyesore.” Charleston Evening Post, March 27, 1970.

“CPW will be closed Friday to move into new offices on St. Philip Street.” Post-Courier, April 24, 1985.

Butler, Nicholas M., and Kathleen Gray. “Records of the Charleston Police Department, 1855-1991.” The Charleston Archive, Charleston County Public Library, 2008. www.charlestonarchive.org/collections

Fick, Sarah. Sword Gate House, Connections. Charleston: Thomas S. Tisdale, 2002.

“The Police Force.” Year Book, City of Charleston, 1887. Charleston, 1888.

Ravenel, Beatrice St. Julien. Architects of Charleston. Charleston: Carolina Art Association, 1945; rev. 2nd ed. 1964.

Severens, Kenneth. Charleston: Antebellum Architecture and Civic Destiny. University of Tennessee Press, 1988.

Waddell, Gene. Charleston Architecture, 1670-1860. Charleston: Wyrick & Company, 2003.

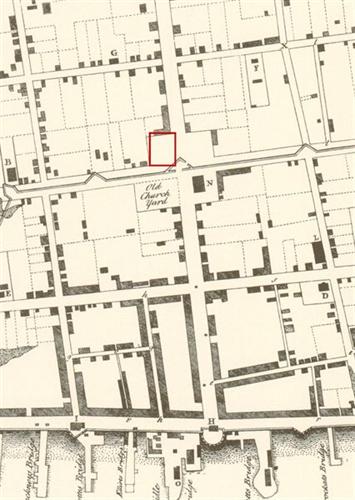

The southwest corner of Meeting and Broad streets was vacant in 1739. |

1788 map view facing east along Broad Street. The 1767 Guard House is the corner building marked "E," identified here as Treasury & Auditor General's Office. The building marked "D" was the Arsenal or Armory identified here as Guard House. Over time, the Guard House and Armory became one property. |

Sword Gate, 32 Legare Street |

Architect’s rendering, “U.S. Post Office Building, Broad & Meeting Streets, Charleston SC,” 1888. Charleston architect John Henry Devereux designed the building, and a series of federal architects managed construction drawings and specifications. |

United States Post Office, 83 Broad Street, completed in 1897. |

United States Post Office, 1909 postcard view from the south. |

Charleston Police Station, opened 1888. Contractors J. D. Murphy and D. A. J. Sullivan completed the new Central Police Station for the cost of $43,000. The architect was Louis J. Barbot, longtime chief engineer for the City of Charleston. |

Central Police Station and The Citadel, 1902. |

Early twentieth century postcard view of The Citadel from Meeting Street shows the 1887 police station. |

Ironwork from the 1887 station house was taken to The Citadel’s new campus in 1922 and installed at the Summerall Gate (shown here) and the pedestrian gates at the main Lesesne Gate. |

Charleston Police Station insignia on The Citadel’s Summerall Gate. |

In November 1960, the Charleston County Public Library, 404 King Street, opened on the site of the 1887 police station. The library building was razed in the summer of 2013. |

Completed by building contractor J. T. Snelson, the Central Police Station had a granite base and cement finish. City Council’s Committee on Public Safety thanked the architect, R. Thomas Short, for “giving to the city one of the handsomest police stations in this part of the country.” |

Charleston Police Station, opened January 1908. “There is perhaps only one feature of the appearance of the building that has not been admired, and that is the little turret growing out of the large corner turret at the southeast corner of the building. If someone would come along and knock this knob off the corner, it is thought by the general run of critics that the building would be handsomer. And yet architect Short spent some time in fashioning this particular bit of ornamentation, and considers it the center of the architectural excellence of the station’s lines.” Charleston Evening Post, January 21, 1908. |

Charleston Police Station, 1944. |

Charleston Police Station, 103 St. Philip Street, 1972. |

LoadMainPhoto_490x490.jpg)

Load1788Phoenix_500x500.png)

1909PostcardUSPO_500x500.JPG)

Load1887StationHouse_500x500.png)

1902PoliceStationSanborn_500x500.jpg)

DetroitPublishing_500x500.jpg)

LoadGate_500x500.png)

LoadGateDetail_500x500.png)

OldLibrary,1960_500x500.jpg)

Postcard1908policeStation_500x500.JPG)

Load1916YearBook_500x500.png)

1944Sanborn_500x500.jpg)

1972FWStationHouse_500x500.jpg)