| 79. Washington Race Track 1792-1900 |

|

||

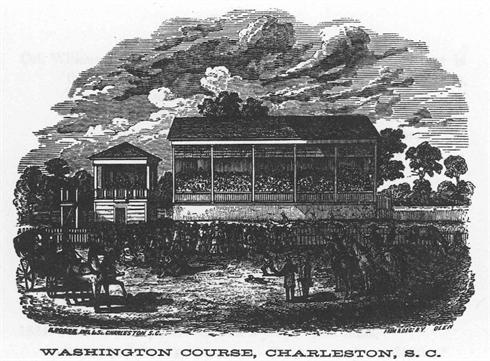

The grandstand on the north side of the course was erected in 1836. This 1857 view of the grandstand was published in John Beaufain Irving's The South Carolina Jockey Club. |

From 1792 until 1882, the Washington Race Course, a one-mile loop around today's Hampton Park, featured the finest horse racing in the South. The track was a venture of William Alston, William Washington, and other breeders of thoroughbred racehorses, who bought a portion of The Grove farm on Charleston's rural upper peninsula. The August 1791 purchase provided a new venue for the South Carolina Jockey Club, which vacated its former course at New Market.

The course was ready by Race Week, February 1792. The main event was the Jockey Club Purse, a race of four heats. Typical of eighteenth and nineteenth century flat racing, events featured a grueling series of "heats" contested by the same horses and riders. A race might be two, three or four one-mile heats. Excitement rose with each run, as horses fell lame or upset earlier winners. Between heats, while the grooms rubbed down the sweating horses, spectators made new wagers and traversed the grounds in search of other entertainment. (Hurdle races were not galloped in heats; the danger inherent in jumping the obstacles just one time around was thrilling enough.)

For seventy years, Washington Race Course came to boisterous life for a week in February, with racing on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Tavern-keepers rented houses near the track to use as restaurants, bars and inns. Other entrepreneurs erected smaller structures: in 1807, Christian Booner advertised that he had "taken his former stand opposite the starting post, where his table will be provided with the best the markets afford and choicest liquors during the race week and on Monday following. Mock Turtle soup every day." Ladies remained in the grandstand, enjoying treats fetched by their own slaves or the gentlemen who roved among the nearby refreshment rooms or booths on the outside of the course. There they mingled freely with gamblers, slaves, traveling salesmen, and others excluded from refined areas.

Watching horses was only part of a day at the races; there was a wide variety of other amusements. The track and infield provided a showplace and sales arena. There were often public auctions of real estate, and on February 15, 1798, Laurence Campbell sold "a field wench with her two children, one a boy about 10 years old, and the other a girl about 8 years old" on the course. More pleasant were such attractions as the "Learned Pig" whose tricks were on view in 1804, or the 1838 sale by Mr. Porcher of eight thoroughbred horses recently imported from England.

The Jockey Club's historian, John B. Irving, described Race Week as the "carnival of the state." Beginning in the 1820s, crowds packed the course on non-racing days to watch militia demonstrations. On 1823, Governor Wilson reviewed General Geddes's 4th Brigade, who "exhibited a handsome and martial appearance." Such events, including mock skirmishes, continued until the Civil War.

Race Week was the apex of Charleston's winter social season. Handsomely funded by dues and investment income, the Jockey Club hosted a dinner on Wednesday and a Friday night ball. Invited guests included non-members with good social connections, both local and out-of-town families. Private balls in downtown mansions filled out Race Week's other evenings.

The breeders of most entries at Washington Race Course were South Carolina planters. Families of horsemen such as the Alstons, Stoneys, McPhersons, Sinklers, and Singletons were joined by Wade Hampton, whose nationally-known Millwood stable was just outside Columbia; the Canteys, who raced mostly in Camden and Stateburg; the Richardsons of Sumter District; and planters from Virginia, Georgia, even Kentucky and Louisiana. Many stabled their entries at the course, while horses kept behind their owners' townhouses walked to and from the track, cheered along the route by throngs of children.

Occasionally a man rode his own horse, but most jockeys were of a different social order, and many of them were slaves. However, races were segregated by gender, age, or experience of the horse, not by the status of the rider: an 1859 match race saw Planet, a Virginia horse ridden by Mr. Frank Hampton, beating the South Carolina mare Hennie Farrow under "a boy" in two heats. Successful breeders relied on the abilities of their slaves in raising, training, and riding their thoroughbreds. After working as jockeys or grooms, a few slaves became respected trainers in their own right. Richard Singleton's bondsman Cornelius was "a feature in the crowd upon a race field" for thirty-five years, and William Sinkler's Hercules, a renowned trainer and "one of the most faithful colored grooms in the state," trained John Cantey's mare Albine, which won the final Jockey Club Purse, on February 6, 1861.

Washington Race Course and the nearby Grove Farm [Lowndes Grove] were unpopulated most of the year. From an early date, the isolated setting provided a dueling ground. Numerous duels, fatal and non-fatal, were recorded. Writing for the New York Times in 1913, Charleston newspaperman J. C. Hemphill gushed that "in those days, there were blooded men in South Carolina as well as blooded horses." However, nineteenth century duelists included not only such pedigreed gentlemen as John McPherson, J. Davidson Legare, Alfred Rhett, and Arnoldus Vanderhorst, but also working-class hotheads. In 1834, the Southern Patriot reported a duel "behind the Race Course this morning." The combatants were Francis Boutain, barkeeper at Mrs. Chapee's boarding house, and one of her boarders. "The former was shot through the heart at the first fire, and instantly expired."

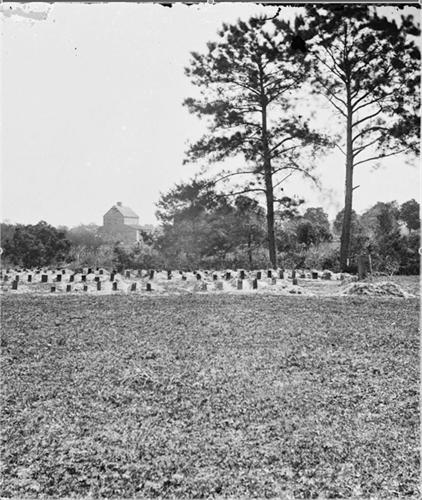

During the Civil War, Washington Race Course became a camp for Union prisoners of war. The death rate in the open field was frightful - at least 257 men died, and were buried in unmarked graves. After Union forces occupied Charleston, the dead were exhumed and reburied under respectful markers. In April 1865, freedmen built a fence around the burial ground, with an arch reading "Martyrs of the Race Course." On May 1, 1865, thousands of African-Americans - freed slaves, children, Union soldiers - made a procession to the cemetery. They laid flowers on the graves, listened to speakers of both races, and picnicked on the grass. This celebration was America's first Memorial Day. The martyrs of the racecourse were exhumed again in 1871 for proper military burial in South Carolina's national cemeteries at Beaufort and Florence.

In 1875, the South Carolina Jockey Club reorganized and printed a revised rulebook. More than 100 members paid dues in 1876. At that time, the club had two tangible assets: its real estate, and a large cache of valuable Madeira wine that had survived the Civil War hidden on the grounds of the South Carolina Asylum in Columbia. The sale of the wine in 1877 allowed the club to refurbish Washington Race Course and begin a new season of horseracing.

The February 1878 races were spread over four days, two of them Saturdays. Despite low attendance, Charleston again became a regular stop on the flat racing circuit. There were entries from several states in 1879, and in December 1880 the Jockey Club added a winter meet. By 1881, improved tramline connections made a convenient circuit between downtown and the Washington Race Course. However, breeding fine thoroughbreds had become an impossible luxury for lowcountry planters. Declining entries combined with a series of cold, wet Februarys to strip Race Week of its social cachet. With low attendance and low gate receipts, the Jockey Club could not continue the races. Racing took place for the last time in February 1882. In 1884, the racecourse grounds were leased to J. H. West as farm/pastureland.

Although there was no longer Jockey Club-sanctioned thoroughbred horses racing in Charleston, in 1883 a new racetrack just north of the Washington Race Course filled the entertainment gap. The Charleston Driving Association's half-mile course on F. W. Wagener's farm was the scene of harness and flat racing into the early twentieth century.

In 1899, the twenty-six members of the South Carolina Jockey Club finally voted to disband. The club's remaining assets - the race course and adjoining farm, along with $13,500 in securities and cash - were deeded to the Charleston Library Society. In 1900, the society rented the grounds to the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition, then sold the land to the City of Charleston.

From 1792 until 1861, periodic improvements and alterations to Washington Race Course are recorded in newspaper advertisements, and in John B. Irving's South Carolina Jockey Club. The first extensive work, after clearing the course, was to install "about 5000 feet of a post and rail fence, with a ditch so as to enclose the whole of the land belonging to the proprietors in a good and workmanlike manner as the new fence that is now done on the front of that land." From at least 1793, the owners leased the course out for livestock grazing year-round, requiring the tenants to maintain the fencing and to move off the grounds during Race Week.

In 1831, a seven-foot fence was constructed around the outside of the track, restricting sight of the races to those who paid an entry fee. Always conscious of social proprieties, the Jockey Club deemed that "respectable strangers from abroad or from other states are never allowed to pay admission… they are considered guests." In 1836, noted architect Charles F. Reichardt designed a new grandstand and other buildings for Washington Race Course, and in the late 1840s the Jockey Club purchased a twenty-three acre farm adjoining the course to provide stabling and pastures for out-of-town contestants.

When the Charleston Library Society rented the Washington Race Course to the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition in the early twentieth century, its fencing and most of the buildings were razed. After the exposition closed, the City of Charleston paid the Charleston Library Society $32,500 for the land, seventy acres of high ground and twenty acres of marsh. The racecourse entry posts became surplus property when the parcel was redesigned as Hampton Park. In 1903, August Belmont, Jr., a New York racehorse owner and part-time South Carolina resident, asked to buy the four piers. The City of Charleston, instead, offered them as a gift. The brick posts were boxed and shipped to New York, to be repaired and reinstalled at the new Belmont Park on Long Island, New York. On Belmont's opening day, May 4, 1905, nearly 40,000 people streamed through the South Carolina Jockey Club gates.

The oval track of the Washington Race Course remains as the bed of Mary Murray Drive, which encloses Hampton Park. The road was improved and paved in 1924, with funding by philanthropist Andrew Buist Murray, and named in memory of his wife, Mary Hayes Bennett. Simple stuccoed gateposts stand at the Cleveland Street entrance to the park.

Behre, Robert. “Charleston Pillars Greet Belmont Fans.” The Post and Courier, June 13, 2005.

Clinton, Catherine, editor. Honoring Fallen Soldiers: America's First Memorial Day. May 1, 1865, Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston, 2002.

Eberle, Kevin R. A History of Charleston's Hampton Park. Charleston: The History Press, 2012.

"Fine Sport on Course." News and Courier, February 7, 1880.

Irving, John Beaufain. The South Carolina Jockey Club. Charleston, 1857. www.googlebooks.com. Rep. ed. Spartanburg: The Reprint Press, 1975.

Hemphill, J. C. "Charleston's Old Race Course a Noted Dueling Spot." New York Times Sunday Magazine, January 26, 1913.

"In Memoriam, Andrew Buist Murray." Year Book, City of Charleston, 1929.

"The Martyrs of the Race Course." Charleston Courier, May 2, 1865.

"Ready for the Races." News and Courier, February 3, 1880.

South Carolina Jockey Club Records. Unprocessed manuscript collection, Charleston Library Society.

Sparks, Randy J. "Gentlemen's Sport: Horse Racing in Antebellum Charleston" South Carolina Historical Magazine, January 1992.

The Ladies' Clubhouse on the north side of the course was erected in 1836. During the late months of the Civil War, Federal officers held captive by the Confederates were confined here. |

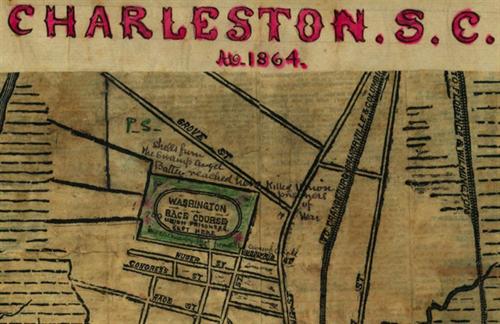

Washington Race Course, 1864 |

1865 view of the Union soldiers graves at Washington Racecourse |

Four piers stand beside Long Island’s Hempstead Turnpike, flanking the clubhouse entrance to Belmont Park. The bronze plaque (left) reads “Presented to Belmont Park May 1903 by the Mayor and Park Commissioners of the City of Charleston SC. At the suggestion of B. R. Kittredge Esq. and through the good offices of A. W. Marshall Esq. These piers stood at the entrance to the grounds of the Washington Course of the South Carolina Jockey Club Charleston SC. Which course was opened Feb. 15th 1792 under presidency of J. E. McPherson Esq. and was last used for racing in December 1882. Theo. G. Barker Esq. being then president.” |