|

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress; from Charles N. Bayless Photos of Charleston, Collections of The Charleston Archive, Charleston County Public Library |

|

Thomas Bee's house, at today's 94 Church Street, survived the 1778 fire, but most of its furnishings disappeared.

For weeks after the fire, the South-Carolina and American General Gazette ran Bee's advertisement: "Lost in removing from my house during the late fire, among many other articles of value, the following: six mahogany chairs with horsehair bottoms, four paintings, a good many books, three large case bottles of Jamaica rum, about fifteen dozen of Madeira wine… Any person who will deliver the articles, or can give information where they may be found, shall receive a reward suitable to the value recovered, and many thanks from Thomas Bee." |

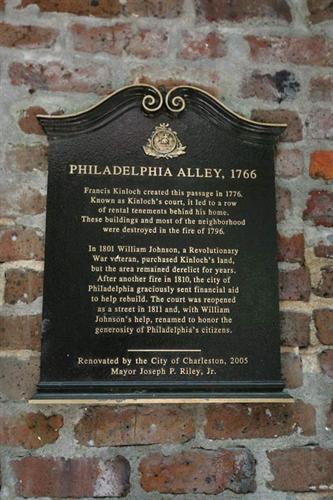

This fire began in the "bake-house of one Moore at the north end of Union Street." Detected at 4:00 AM, January 15, 1778, its progress was arrested by noon, but already more than 250 houses and innumerable outbuildings had been destroyed. The fire and firefighters leveled all of Union (State) Street, most of Chalmers Alley, the south side of Queen Street from Mrs. Doyley's house to the Bay (East Bay Street), and all but fifteen houses along the Bay from Queen Street south to Granville's Bastion. The north side of Broad Street was in ruins from Mr. Thomas Smith's house to the Bay, and the south side from Mr. Sarrazin's to Mr. Guerard's house. Except for five tenements, every building was lost from the east side of Church Street between Broad Street and Stoll's Alley; Tradd Street east of Church Street was equally devastated. Bedon's Alley and Gadsden's Alley were wrecked, and only two houses remained in Elliott Street. Six people, white and black, had been killed. The Charleston Library Society's leased building in Kinloch’s Court (Philadelphia Alley) was destroyed, along with most of its “valuable collection of books, instruments and apparatus for astronomical and philosophical observations and experiments.” The chaos of a night fire in eighteenth century Charleston was compounded by the raw fear of residents. People whose dwellings were in the path of the approaching blaze rushed their belongings to the street, trusting firefighters, neighbors, and slaves to carry their goods through the dark streets to a safer place. Thieves rushed in to abscond with valuable possessions under pretext of salvaging the articles. All the while, the Firemasters were observing the wind and the direction of the flames, selecting which houses would be torn down or blown up to create fire breaks. As happened with most fires, soldiers and mariners played an essential role in stopping the conflagration of 1778. The South-Carolina and American General Gazette offered "much praise to the officers and soldiers quartered in town, who afforded every assistance in their power to the inhabitants…. Capt. Biddle, with a party of his crew, also assisted, as did most of the masters and sailors belonging to the other vessels in harbor." Sailors and soldiers manned the pumps and destroyed houses as directed, while homeowners scurried to protect their families, slaves, animals, and movable goods. In just one day, hundreds of families were dispossessed. The wealthy and well-connected arranged to rent houses, store their belongings, and provision their kitchens. The less fortunate found themselves destitute in midwinter, without food or shelter. The evening after the fire, it was announced that lodgings and victuals would be provided, at public expense, in the city's public buildings. The next day, South Carolina's General Assembly voted £20,000 for the immediate relief of the sufferers. For weeks after January 15, people who had lost expensive articles advertised for the return of goods - chests, clothing, rum, wine, books, jewelry, shoes, furniture, paintings - that had been hauled out of their houses in the race against destruction. Others placed notices of new business locations. Eleanor Potter, burned out, "now lives at Mrs. Stone's, opposite the printing office in Tradd Street, where she carries on the staymaking business as formerly." Jane Stewart, driven from her house in Tradd Street, moved to the Play house, where "she will be glad to accommodate a few gentlemen with board and lodging." James Witter, Jr., moved his store and counting house to the "house where he lives in Church Street, opposite Stoll's Alley and near Young's Bridge, being very convenient to land indigo." Other businessmen had a more difficult time finding a new location. William Cunnington, "burnt out and reduced to a state of indigency," could not immediately find a place to set up his factorage office. The trustees of the Old Baptist Meeting House allowed him to carry on his business there, where he offered for sale a few casks of indigo, promising to get any quantity a customer might desire on a few days notice. These newspapers advertisements seem to belie the fact that the American colonies had been at war with Britain for nearly two years. However, in early 1778, the battles were being fought in northern states far from the Lowcountry, while Charleston's continuing commerce provided the ready money needed to carry on a war. Colonial South Carolina had sent rice, indigo, and deerskins to the English market; independent South Carolina exported to other European countries, especially France and Holland, and imported weapons, ammunition and gunpowder through Charleston. Many of the men who fought the fire on January 15, 1778, were the crews of trading vessels soon to sail for Europe. Borick, Carl P. A Gallant Defense, The Siege of Charleston, 1780. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003.

Crooks, Daniel J., Jr. Charleston is Burning. Two Centuries of Fire and Flames. Charleston: The History Press, 2009.

South-Carolina and American General Gazette, issues beginning January 29, 1778.

|

1788Phoenix_500x500.jpg)

50Broad_500x500.jpg)

50BroadEtching_500x500.jpg)

CLS_1914_medium_500x500.jpg)

ArchitectElevationCLS_500x500.jpg)

Charleston_Library_Society2010_500x500.jpg)