|

| Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ |

|

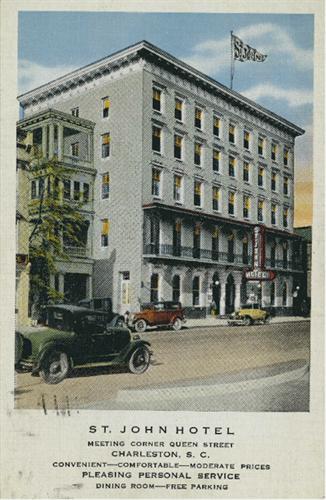

When President Theodore Roosevelt visited the South Carolina and West-Indian Exposition in 1902, he stayed at the St. John Hotel.

|

Built in 1853 at the southwest corner of Meeting and Queen streets, the original Mills House hotel was named for its owner, wholesale grain merchant Otis Mills (1794-1869). Designed by architect John E. Earle and built by contractors James P. Earle and R. Earle at an estimated cost of $200,000, the five-story building had an iron balcony across the façade, ornate terra-cotta cornices above the windows, and an arcaded entryway. A few weeks before the hotel opened, a reporter for the Charleston Courier visited the new building. The resulting article, a feature-by-feature tour, ran to nearly a full page, the reporter being overwhelmed in equal measure by the Mills House's grand scale and by its modern equipment. Much of the architectural trim was imported: the ironwork, marble mantels, and chandeliers from Philadelphia; stoves and furnaces from New York, furniture from Boston. However, the stone and marble work for pavement and exterior steps were locally supplied by W. B. White. The hotel boasted a dining saloon, a gentlemen's dining room, a second-floor ladies "ordinary" with tables for 160, and 180 guest rooms. Gas lighting illuminated every room, and on each floor were eight "bathing rooms" for ladies; similar rooms for gentlemen were found on the first floor. Water for the baths, steam heating system, and in-house laundry would be supplied by wells and cisterns on the property.

Thomas S. Nickerson, an experienced hotelier, leased the completed Mills House from Otis Mills. Their five-year agreement covered the hotel and outbuildings; Nickerson paid separately for the furnishings, wine, liquor, and other supplies. His lease terms must have been too expensive, for in mid-1857 Otis Mills negotiated a new three-year contract with Joseph Purcell, whose yearly payment was about half what Nickerson had committed to. For $7,500 annually, Purcell had use of the Mills House and outbuildings, as well as the brick house next to Hibernian Hall, which was "fitted up and used as a bar room and billiard saloon." He paid a further $17,000 for all the furniture on the premises. Purcell and Nickerson might already have had a working relationship; in 1862 the two were joint proprietors of the Mills House.

Dozens of people, white and black, free and slave, found employment at the Mills House. William Inglis, a free man of color who worked as a barber in the hotel, earned enough that by 1856 he and his wife Elizabeth were able to buy the house at today's 46 Anson Street (Otis Mills acted as their trustee for the purchase).

The Mills House hotel was not the first commercial establishment at this corner, property which was part of "Archdale Square." The building it replaced, a double three-story brick house, had traditionally accommodated both residential and commercial use. While John Paul Grimke (d. 1791) and his family lived in the house, known as 101 Meeting Street, milliners or similar tradesmen rented the cellar and two "elegant rooms, with fireplaces." Grimke's daughter, Mary, eventually inherited his house and outbuildings, including a "back store" on Queen Street. When Henry Ward married Mary Grimke, he assumed management of her estate.

Henry Ward signed an agreement with hotel operator Francis St. Mary in June 1801, and on December 24, 1801, the South-Carolina Gazette ran a notice: "St. Mary's Hotel this day removed to that eligible situation and commodious house, the corner of Meeting and Queen streets, formerly occupied by Mrs. Miott, as a genteel boarding house. Gentlemen accommodated with boarding and lodging, or boarding alone. Breakfasts, dinners, etc. Soup every day - and suppers, beef steaks and oysters every evening, and in private rooms for select parties."

It is not clear how long Mrs. Frances Miott had kept her boarding house in the Grimke house. The Charleston City Directory for 1802 shows that she had moved her business to Champney's [Exchange] Street. At the end of the year, Francis St. Mary relocated to the former Brockway's tavern on King Street, and Mrs. Miott temporarily returned to the Grimke house.

On October 1, 1803, James Thompson, previously proprietor of the Carolina Coffee House, opened The Planters Hotel in "that large airy and commodious building lately known as St. Marys Hotel, to accommodate country gentlemen and their families with boarding and lodging... His larder will always be furnished with the best the markets afford, and his liquors will be genuine and of the first quality." Thompson's tenure at the corner of Meeting and Queen streets was brief. In 1806, Mrs. Alexander Calder leased the property, and "spared no pains nor expense" to upfit it for the "reception of the gentlemen planters from the country, as also for the citizens of Charleston, in a style that unites comfort, neatness, and convenience." The house was newly whitewashed and painted, and all fourteen rooms featured new furniture, bedding, and carpeting. Mrs. Calder and her husband were ambitious, and within a few years they also took over a boarding house on Sullivan's Island. In 1809 they moved the Planters Hotel to the corner of Church and Queen streets (today's Dock Street Theatre).

Mary Grimke Ward kept her parents' home as income property until her death in 1822, bequeathing "my two houses, one corner of Meeting Street and Queen, the other in Queen Street," to be divided among the children of her brother John F. Grimke. In 1825, the siblings, who included the well-known abolitionists Angelina and Sarah Grimke, sold the house to Plowden Weston (d. 1827), whose Queen Street residence stood on the adjoining parcel. Weston's sons sold the Grimke house and lot to Otis Mills in 1836.

During the early 1840s, the United States Courthouse had offices in the Grimke house, and at least from 1848-1852, the building was known as the Mansion House hotel. During this time, Otis Mills was acquiring the neighboring parcels on Meeting and Queen streets. These six purchases brought his lot to 130'X275', large enough to build a substantial replacement for the Mansion House. In October, 1852, Mrs. Jane Davis, proprietor of the Mansion House, relocated her business from the corner of Meeting and Queen streets to "that pleasantly located house on the south side of Broad Street, formerly known as Jones Hotel."

During the Civil War, Otis Mills sold most of his real estate for investment in Confederate bonds. In April 1863, he sold the Mills House to Joseph Purcell and T. D. Wagener for $13,500 Confederate dollars. Purcell was still the proprietor of the Mills House in 1867, but its operation for the next several decades is unclear. After Otis Mills died, in 1871 the hotel was sold at auction subject to a lease through October, 1873. In 1874 George W. Williams sold the property to John Hanckel, Robert Douglass, Eri H. Jackson, and Merritt P. Pickett; in early 1901 their heirs and executors conveyed it to Rosa L. Douglas of Atlanta.

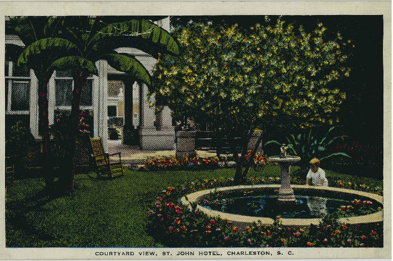

Rosa Lawton Douglas (1834-1916) was the niece of St. John Alison Lawton, a James Island dairy farmer. Her acquisition of the Mills House was a family endeavor: soon after the purchase, Lawton and architect Rutledge Holmes solicited contractors' bids for remodeling the building into an apartment house. The plans were not executed, and Mrs. Douglas sold the property to Cecilia Lawton, her grandmother. The elderly Mrs. Lawton was a successful businesswoman, owner of Battery Dairy, the downtown bottler and distributor of the family's milk. She renamed the Mills House "St. John Hotel" after her son, and kept a sharp eye on its managers before selling the property in 1907. It remained in the buyer's family for decades.

The St. John Hotel suffered from the competition of the new Francis Marion and Fort Sumter hotels, both opened in 1924. Although Charleston's growing tourism industry assured its survival into the 1960s, revenues did not provide for modernization or even routine upkeep. The dilapidated structure was sold at public auction in 1968. The buyers, Charleston Associates (Richard H. Jenrette, Charles D. Ravenel, and Charles H. P. Duell) planned to rehabilitate the historic building.

Renovation of the Mills House proved infeasible, and the owners decided to demolish it and replace it with a close replica (a notable difference being the increase from five stories to seven). Architects Curtis and Davis of New York designed the hotel, Ruscon Construction Company was the general contractor, and local architects Simons, Lapham, Mitchell and Small consulted on exterior design and historic detail. Under their supervision, the original iron balcony was salvaged for reinstallation on the new structure, and elements of the original terra cotta window pediments were stored in the basement of Hibernian Hall so reproductions could be cast. The modern Mills House Hotel registered its first guests on October 9, 1970.

Charleston City Gazette, various dates.

"The Mills House." Charleston Courier, August 13, 1853.

"Otis Mills, Esq." Charleston Courier, October 25, 1869.

"The Mills House at Auction." Charleston Courier, January 9, 1871.

"St. John Hotel on Historic Site." News & Courier, January 16, 1937.

Bresee, Clyde. Sea Island Yankee. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 1986; rep. ed. Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 1995.

Hill & Swayze's Confederate States Railroad & Steamboat Guide… Complete Guide to the Principal Hotels.... 1862 (electronic edition in Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

Ravenel, Beatrice St. Julien. "John E. Earle." Architects of Charleston. Charleston: Carolina Art Association, 1945.

Simons, Harriett P., and Albert Simons. "The William Burrows House of Charleston." South Carolina Historical Magazine 70 (1969).

Wells, John E., and Robert E. Dalton. "Holmes & Lawton." The South Carolina Architects, 1885-1935. A Biographical Dictionary. Richmond: New South Architectural Press, 1992.

|