Charleston's first purpose-built storehouse for gunpowder was the Old Powder Magazine, within the town's fortification wall on today's Cumberland Street. During the 1730s, lessening fears of attack by the French, Spanish, and Native Americans allowed settlement beyond the walls, and led to the decision to construct a powder magazine in a less-populated area. In 1737 the new magazine was built on the "Old Burying Ground," the block bounded by today's Queen, Franklin, Logan and Magazine streets. The structure proved so poorly built that it was abandoned within a few years, and the gunpowder supply was returned to the Old Powder Magazine.

In 1748, another magazine was constructed near the site of the 1737 structure. Large enough to hold 50,000 pounds of powder, and said to be "bombproof," this powderhouse was set among the Common Gaol, Workhouse, and other public buildings. It gave its name to Magazine Street.

With development in the surrounding area came fresh worries about the risks to public safety posed by stored explosives. To remove the hazard, new magazines were built in 1772 at Shipyard Creek on Charleston Neck and Hobcaw Point east of the Cooper River. When they were finished, the "powder in the Magazine at Charlestown [was] removed thither and kept there, and thenceforth the said Magazine at Charlestown shall no longer be occupied as such."

During the Revolutionary War, this "Town Magazine" and the Old Powder Magazine on Cumberland Street were repaired and stocked with gunpowder. In 1779, the public Powder Receiver spent £583.6.6 repairing the "Town Magazine," which would supply gun emplacements along the Ashley River from Battery Northwest to Oyster Point. A fortification on the Burying Ground lot near the magazine was named for it, DeVieux ["the old"] Magazine Battery.

Both downtown magazines were emptied again after the British capitulation. South Carolina's Governor and Council ordered most powder to be kept at Shipyard, and "only the smallest necessary part in Town Magazine, in order to discharge the city from danger thereof." But in 1788 the public Powder Inspector, Major A. M. Muller, requested permission to revive the downtown magazine, claiming that the Shipyard Creek storehouse was so inconvenient that importers and merchants were keeping dangerous quantities of powder concealed in buildings and aboard ships. He was authorized to keep no more than 5000 pounds in town.

There were ongoing problems with the Shipyard Creek magazine, but it was retained as a holding place for all except the 5000 pounds stored at the Town Magazine. Although the "Workhouse" magazine was repaired in 1800, by 1808 it had been discontinued as a public magazine and was never reused.

After years of legislative acts and public inaction, extensive deterioration of the Shipyard Creek magazine forced the city to reopen the Old Powder Magazine on Cumberland Street in 1820. Finally, in 1821, the state legislature appropriated $8,000 for a new magazine at Charleston. The new State Magazines near Newmarket Creek were completed in 1823. The “Dead House” at Chicora Park South of Noisette Creek (in today’s North Charleston) is a brick structure that for years has been called the "Dead House," on the assumption that it must have been a private mausoleum. It is more likely that the building, constructed as a vault with strong exterior buttresses, was designed as a powderhouse. Its location on Retreat Plantation, which was owned from 1771 to 1778 by Sir Edgerton Leigh, the colony's Powder Receiver, support that view.

The Olmsted firm of landscape architects retained the Dead House when they laid out Chicora Park for the city of Charleston. Through a century of federal ownership of the Charleston Navy Yard, the building was treated with benign neglect; it was identified as a significant historic structure during the base closure process. “Charleston Navy Yard Officers’ Quarters Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, S. C. Dept of Archives and History, 2006. http://www.nationalregister.sc.gov/charleston/S10817710176

Davis, Nora M. "Public Powder Magazines at Charleston." City of Charleston Yearbook, 1942.

Guy, Randy L. "Rediscovering History at the Charleston Navy Base." Preservation Progress, for the Preservation Society of Charleston, Vol. 36, No. 3, Winter 1994.

Ohm, Christopher A. "The Dead House at the Former Charleston Navy Yard and Shipyard: Searching for Answers." Master's Thesis, Historic Preservation, Graduate School of Clemson University, May 2007.

“Report of Park Commissioners.” Year Book of the City of Charleston, 1899.

|

|

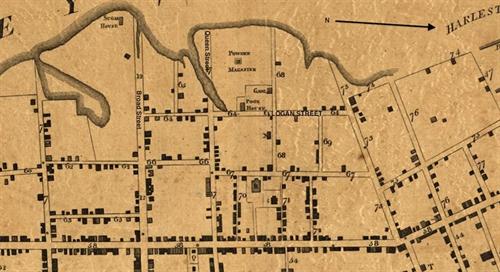

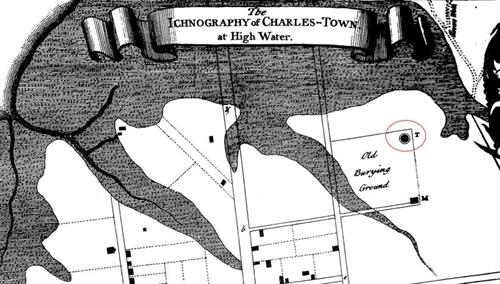

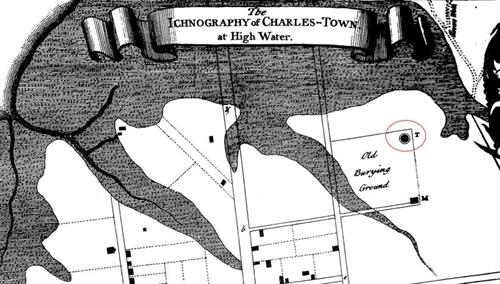

| Bishop Roberts and W. H. Toms, The Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water. London, 1739. |

Shown on Bishop Roberts' 1739 map as "T," the new powder magazine was built on public land west of the Work House ("M").

|

NewPowderMagazine1780_500x500.jpg) |

| “Sketch of Operations Before Charlestown Copied from Sir Henry Clinton’s Map, 1780.” Courtesy of Alabama Maps http://alabamamaps.ua.edu |

Town powder magazine in 1780.

|

|

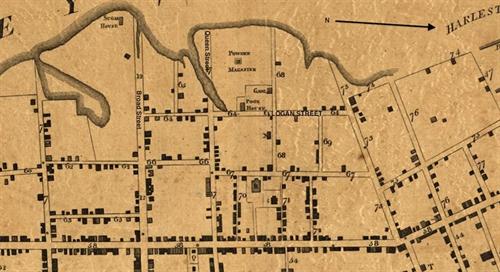

| Edmund Petrie, Ichnography of Charleston, South Carolina. London, Phoenix Fire Company, 1788. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

Town powder magazine on public land, 1788.

|

|

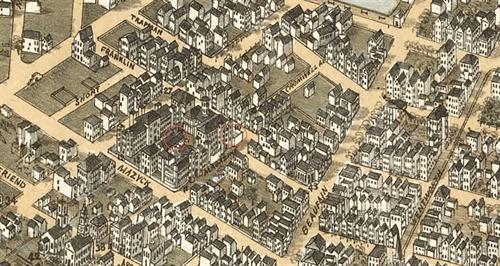

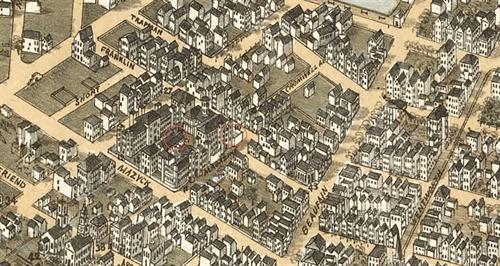

| C. Drie. Bird's Eye View of the City of Charleston, South Carolina. 1872. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

Location of the “new magazine” and the “old magazine battery” in 1872. The fortifications had made way for the City Jail and hospitals.

|

|

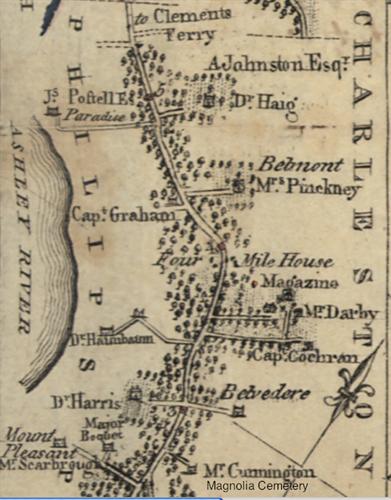

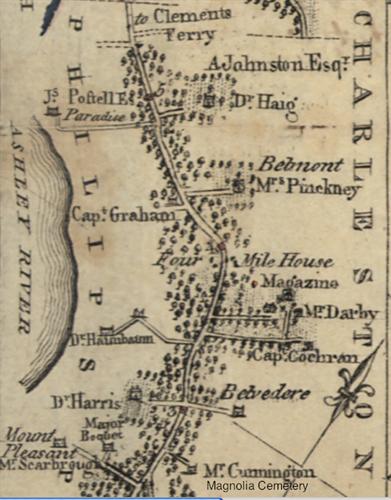

| Road to Watboo Bridge, from Charleston, by Goose Creek Bridge & Strawberry Ferry. 1787. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

Shipyard Creek Magazine, 1787.

|

|

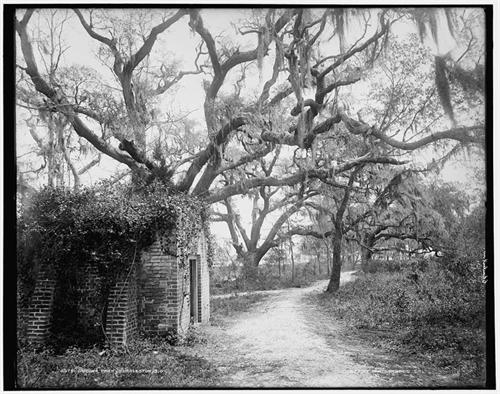

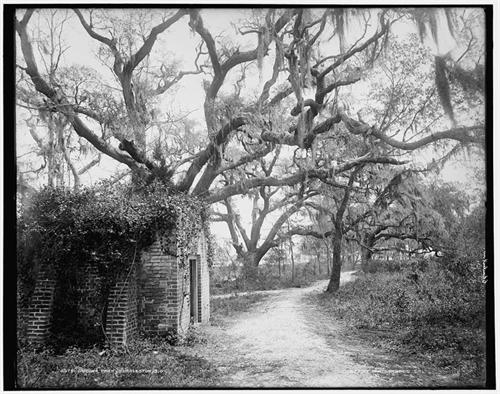

| Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ |

"Chicora Park." Ca. 1901 postcard view showing the Dead House.

|

|

| Joel Gascoyne, “A new map of the country of Carolina.” Ca. 1682. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

General area of Marshlands and Retreat plantations, 1682.

|

|

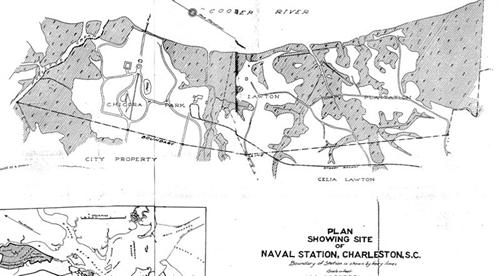

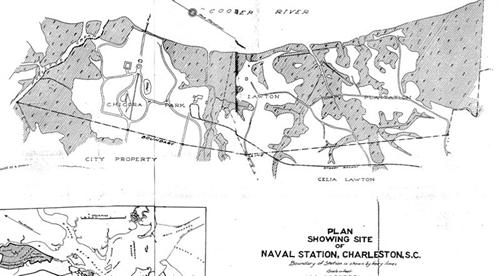

| Year Book of the City of Charleston, 1901 |

Chicora Park was laid out on Retreat Plantation; the Charleston Navy Yard comprised Marshlands Plantation as well as Chicora Park. The “Dead House” powder magazine remains at the edge of the Retreat tract.

|

|

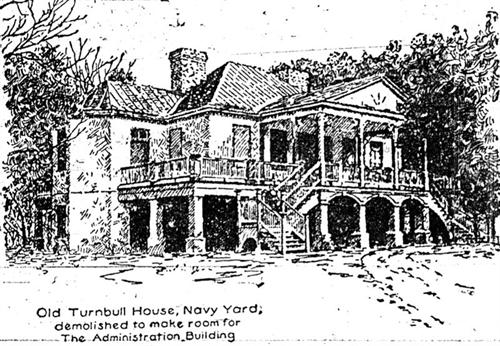

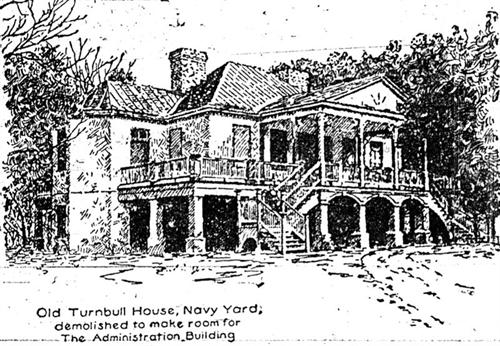

| News and Courier, January 24, 1904 |

The Turnbull House on Retreat Plantation was demolished, and its grounds redeveloped as Naval Officer’s Quarters.

|

|

| Preservation Society of Charleston |

2009 view of Marshlands Plantation House. The U. S. government retained this building on the Charleston Navy Yard until 1961, when it was moved to Fort Johnson on James Island.

|

|

NewPowderMagazine1780_500x500.jpg)