| 1838 (April 27-28) Fire |

|

||

"The renovation and restoration of our fair city is now the all-engrossing topic." Daily Courier April 30, 1838. |

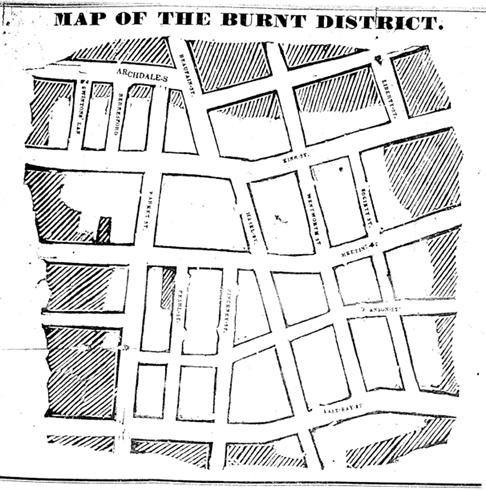

The great fire of 1838 leveled "at least one-fourth of the centre of our beautiful and flourishing city," nearly 150 acres at the heart of the commercial district. More than 500 properties burned, at least 1100 buildings altogether - dwellings, tenements, boarding houses, stores, churches, workshops, kitchens, stables and sheds.

The fire began on the evening of April 27, in a shed behind Mrs. Babson's house at the corner of King and Beresford [Fulton] streets. By 10:00 PM, it had crossed to the east side of King Street, and structures were being demolished to create firebreaks. At midnight, blazes raged down the south side of Market Street toward Meeting Street, and at 2:30 Saturday morning "the Public Markets as far as Church Street were gone…, all the buildings on the south side of Market, the new Stores on the Burnt Lands, the splendid new hotel, …both sides of Meeting as far as Hasell Street - all, all are in ruins." The fire had roared down Hasell, Society, and Wentworth streets, all the way to the Cooper River wharves.

Newspaper coverage began at once, and there were mistakes. The Mercury first stated that the fire broke out "at Sutcliffe's bakery, west side of King Street at the corner of Swinton's Lane [Clifford Street]." James H. Sutcliffe angrily refuted the report that the fire originated on his premises, "which was not the case; it having commenced in a shed five doors to the south." He also corrected the Courier's statement that "my bakery was owned by Maj. Black, which is not the case - the houses and lots belong to me." Contemporary lists of property losses were generally accurate, but it is certain that errors were inserted into Charleston's architectural record.

Press attention focused on public buildings. On Meeting Street, the Masonic Hall building still under construction, and the new Charleston Hotel, complete but not yet open for guests, were gone; between them, Frederic Tudor's brick ice house survived. The New Theatre suffered little damage, due to prodigal use of water-pumping engines, but the nearby Aetna Fire Engine House was destroyed. Bennett's Rice Mill was unharmed; the dormant Norton's Rice Mill at the foot of Laurens Street "burnt to the ground."

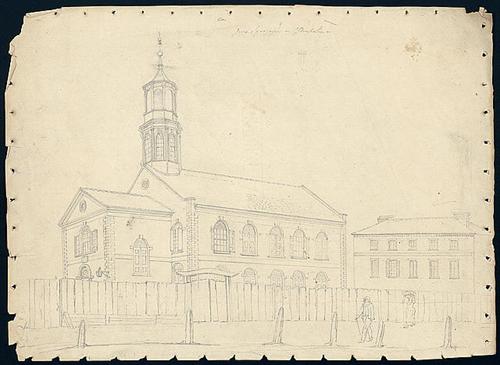

Four houses of worship were destroyed: Wentworth Street Methodist Protestant Church [St. Andrew's Lutheran, now Redeemer Presbyterian], Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim Synagogue, St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church, and Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church. All would be rebuilt, but for more than a year their congregations held services in borrowed buildings. The Methodist Protestants used the Medical College building on Broad Street [the former Charleston Theatre], and KK Beth Elohim met at the Hebrew Orphan Society, also on Broad Street. The Trinity Methodist congregation found space in a "temporary place of worship in the west yard" which the St. Philip's Episcopal congregation had used while rebuilding from the fire of February, 1835.

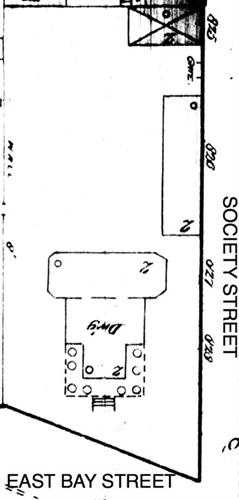

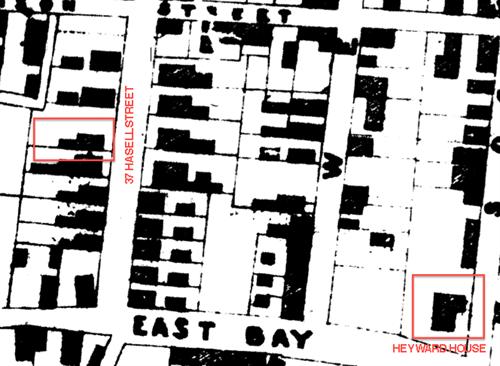

The fire was stopped at two churches on Anson Street: St. Stephen's Episcopal Chapel (the brick replacement for a building on Guignard Street, burned in June 1835), and the Universalist Church, at the corner of Laurens Street. Like the Universalist Church, Augustus Taft's new house at 57 Laurens Street was "saved by the greatest exertions." Taft lost outbuildings, as did Nathaniel Heyward at the corner of East Bay and Society streets, but their wood-frame residences, and John Stoney's sturdy brick dwelling at 54 Hasell Street, were among the few buildings remaining. However, contrary to early reports, the masonry commercial buildings along Pearl [Hayne] Street in the "old burnt district" (the area of the June 1835 fire) were salvageable despite interior damage.

While Charlestonians found emergency shelter for burned-out families, congregations, and businesses, they argued about why the city could not prevent fires, or fight them effectively. The Daily Courier pointed out that King Street's dense collection of wooden buildings, "with here and there a brick house, was always considered to be the most dangerous place for a conflagration to commence, and where, too, was stored a large portion of the most valuable dry goods in the city." There had been little rain, and the water supply in fire wells and cisterns was scant. In such conditions, battling a fire required removing buildings, either with explosives or by pulling them down with fire hooks. Bringing them down to ground level reduced the hazard of windblown sparks, and from cleared lots, fire hoses could play scarce water on adjacent structures.

Yet "there was too much fear of responsibility with regard to blowing up buildings. Orders were seldom given to blow up a building until it was either on fire, or the flames in such proximity, that the execution of the order was almost useless." Even so, the City Engineer did not supply enough gunpowder to carry out demolitions ordered by the Fire Masters. Without bagged powder or prepared charges, the Fire Department was driven to set fuses to kegs of gunpowder - and the assistant chief, Frederick Schnierle, died when a keg exploded. (His brother John Schnierle was on the Board of Firemasters, and became mayor of Charleston in 1842.)

Following the fire, City Council passed a series of ordinances limiting wood construction, and new regulations for managing the duties of the Board of Firemasters, the City Engineer and Fire Department, and the numerous volunteer fire companies. On June 1, 1838, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified An Act for Rebuilding the City of Charleston "to rebuild that portion of the city of Charleston now lying in ruins." A fund backed by state-issued bonds provided construction loans on the "condition, that the money loaned shall … be expended in the erection of brick or stone buildings."

Affordable frame buildings began to go up again in the burned district, and regulations declaring them "public nuisances" to be demolished or fire-proofed, were never enforced. Further, because Charleston's municipal limits did not extend north of Boundary [Calhoun] Street until 1849, the pace of wood construction in neighborhoods such as Mazyck-Wraggborough and Radcliffeborough probably increased. Nevertheless, the fireproof building loan program's legacy is visible in the distinctive Ansonborough neighborhood, where brick residences display a range of 1840s architectural styles.

Charleston Daily Courier, Mercury, and Southern Patriot, beginning April 28, 1838.

"An Act For Rebuilding The City Of Charleston. No. 2744. June 1, 1838" in McCord, David J. Statutes at Large of South Carolina. Volume Seventh, Containing the Acts Relating to Charleston, Courts, Slaves, and Rivers. Columbia, 1840. http://books.google.com/

Crooks, Daniel J., Jr. Charleston is Burning. Two Centuries of Fire and Flames. Charleston: The History Press, 2009.

Pease, Jane H., and William H. Pease. "The Blood-Thirsty Tiger: Charleston and the Psychology of Fire." South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 79 (1978).

Waddell, Gene. Charleston Architecture, 1670-1860. Vol. 1. Charleston: Wyrick & Company, 2003.

Designed by Charles F. Reichardt, the Charleston Hotel was built in the “burnt district” left by the fire of June, 1835. The next great fire, April 1838, destroyed the newly erected hotel. Rebuilt to the same plans, it finally opened in July, 1839. The Charleston Hotel, which spanned the block of Meeting Street between Pearl [Hayne] and Pinckney streets, was demolished in 1960. |

St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church, 89 Hasell Street, 1978. On May 8, 1838, the vestry and members of the Roman Catholic Church of St. Mary agreed to "reconstruct a brick church to be covered with slates or tin, upon the lot where our former church was erected." The building opened for worship in June, 1839. |

Ca. 1812 drawing, KK Beth Elohim Synagogue, built 1792-1794, burned 1838. In 1825, South Carolina architect Robert Mills wrote, “It is a remarkably neat building, crowned with a cupola.” |

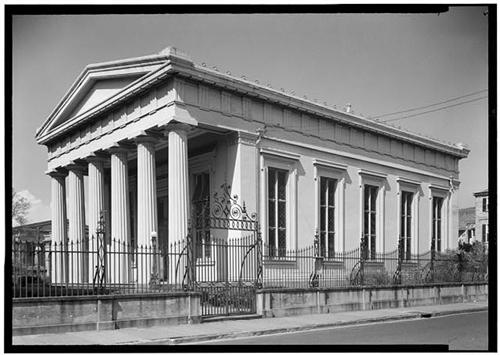

1938 view of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim Synagogue, consecrated March 1841. |

Rhett House, 54 Hasell Street, 1978. This early eighteenth century dwelling known in 1838 as "John Stoney's house" was a rare survivor in the heart of the burned district. |

Nathaniel Heyward House, ca. 1907. Built ca. 1788, this wood-frame house was spared by the 1838 fire. It was torn down in 1917, a few years after the Seaboard Air Line Railway's freight station [Harris Teeter] opened across the street. |

Nathaniel Heyward House, 1884 |

37 Hasell Street, 2009. The Jones-Howell House was erected by building contractors Fletcher & Sessions for Eliza Jones, who financed it with a rebuilding loan from the Bank of the State of South Carolina. |

By 1852, much of the Ansonborough section of the Burnt District had been redeveloped. |