The battery on Coming’s Point was one in a belt of waterfront fortifications "formed of earth and palmetto wood, judiciously placed and mounted with heavy cannon.” These defensive works were constructed early in 1780, when it became clear that the British would attack Charleston from the south and west. On February 22, 1780, General William Moultrie wrote: "I think we ought to have a watchful eye towards Wappoo-cut….; some heavy cannon should be mounted on the west of town, and the creeks about Cumins' stopped." With dikes and ditches, work crews blocked the tidal creeks that flowed deep into the peninsula. Isolated from the populous city, Coming’s Point became an active military outpost. At the end of March, 1780, an entire regiment moved its encampment to “Battery Number One on Cummins Point,” the troops ordered to sleep on their arms. Borick, Carl P. A Gallant Defense, The Siege of Charleston, 1780. University of South Carolina Press, 2003.

"The Siege of Charleston, 1780." Appendix to City of Charleston Yearbook, 1897.

"Order Book of John Faucheraud Grimké, August 1778-May 1780." South Carolina Historical Magazine 13-19 (1912-1920).

Moultrie, William. Memoirs of the American Revolution. New York, 1802; rep. ed. Arno Press, 1968.

|

ComingsPointBattery1780_500x500.jpg) |

| “Sketch of Operations Before Charlestown Copied from Sir Henry Clinton’s Map, 1780.” Courtesy of Alabama Maps http://alabamamaps.ua.edu |

On March 12, 1780, Lord Cornwallis’s troops at Fenwick’s Point (“Mr. Fenwick,” west of the Ashley River) began to fire on American ships. One of their cannonballs landed in the marsh near Coming's Point.

|

|

| Plan de la ville de Charlestown, de ses retranchements et du siege faits par les Anglois en 1780. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

Comings Point Battery, 1780.

|

|

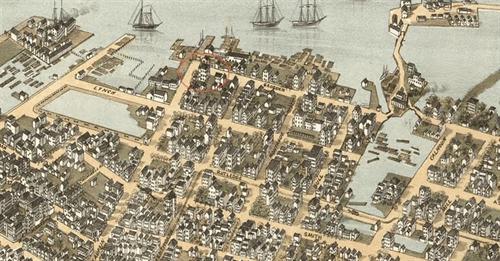

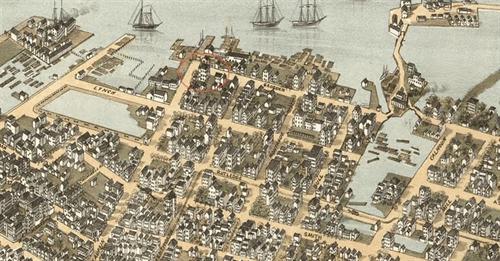

| C. Drie. Bird's Eye View of the City of Charleston, South Carolina. 1872. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

Comings Point, 1872. The area had been developed as the seat of Charleston’s lumber mill industry.

|

|

ComingsPointBattery1780_500x500.jpg)