| 56. West Point Rice Mill 1861 |

|

||

West Point Rice Mill, ca. 1907. |

The West Point Rice Mill was a complex of buildings at the edge of the Ashley River. All the storage and service structures, workshops and residences, have disappeared. Only the four-story brick mill house remains. Construction on this building began in early 1861; it was completed and placed into service during the Civil War.

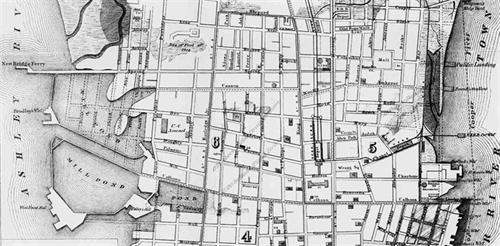

Jonathan Lucas III (1800-1848) built the first West Point Rice Mill on this site, a piece of high ground surrounded by marsh, belonging to his wife's father, Thomas Bennett, Jr. It is not certain when Lucas began construction. The mill must have been nearly complete in September 1841, when Lucas began advertising to hire coopers (barrelmakers).

Thomas Bennett deeded the land to Jonathan Lucas in 1847, and after Lucas’s death, income from the West Point Rice Mill supported his children. In 1853, eldest son Thomas Bennett Lucas (1827-1859) bought the property – land, buildings, machinery, a schooner, and thirty-six slaves – from the estate. T. Bennett Lucas died young, and the West Point Rice Mill was offered for sale as a four-story brick mill with two high-pressure steam engines and storage space for 40,000 bushels of rough rice, a large wooden storehouse, a rice-flour mill, work room for forty coopers, a carpentry shop with its own steam engine, and a blacksmith shop. There were fifteen houses for operatives, residences for the superintendent and millers, and a counting house. The slaves attached to the mill, among them coopers, blacksmiths, and engineers, were to be sold at a separate auction.

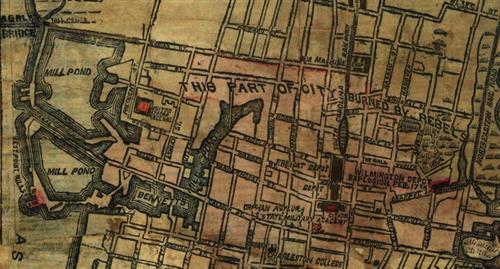

In March, 1860, the “West Point Rice Mill Company,” a partnership of rice planters and factors, paid $97,000 for the land and buildings. This was a prosperous concern, and during autumn harvest season the steam mill operated around the clock, six days a week. Then, on the evening of November 14, 1860, sparks from the rice polishing machine ignited a fire. "Brilliantly illuminating" the west side of Charleston, flames destroyed the mill, machinery, ancillary buildings, and 23,306 bushels of rice. The company was insured, and immediately began rebuilding the West Point Rice Mill. (Because most of the firm's records were discarded during a 1937 renovation, the names of their architect and builders have been lost.)

Despite the onset of the Civil War, the new mill was completed, and received its first load of rice, 102 barrels consigned to Ravenel & Company, in November 1861. However, the milling equipment seems not to have been put into operation during the war. Newspaper reports show that, through the autumn of 1863, the West Point Rice Mill received only barrels of rice, not rough rice to be processed. The property was used chiefly to store polished rice and probably, as federal ships choked off Charleston Harbor, to receive goods landed by blockade runners. During the Union occupation of the city, West Point mill became the main distributing station for rations of rice, grist, and salt.

After the Civil War, rice planters put their fields back into cultivation, but acreage and yield dwindled steadily. By the late 1880s, with three rice mills - West Point and Chisolm's on the Ashley River, and Bennett's on the Cooper River side of the city - Charleston's refining capacity exceeded demand. In 1894 the West Point and Bennett's Mill companies combined forces, bought a controlling interest in Chisolm's Mill, and closed it. The South Carolina rice industry continued its decline, with severe hurricanes in 1893 (August 27 and October 12) and 1911 forcing the final collapse of the iconic crop. The principals of the West Point Rice Mill Company formed a new firm, sold off machinery and equipment, and maintained the property by renting the wharves and warehouses. The business was eventually liquidated.

In April 1926, the City of Charleston paid $75,000 for the forty-three acre West Point Rice Mill site. Mayor Thomas P. Stoney planned an ambitious extension of the Murray Boulevard project, reclaiming mud flats along the west side of the peninsula from Tradd Street to Spring Street. When that idea was abandoned, the West Point Mill property became the heart of a series of projects to be funded by the federal government. Each of these schemes proposed reuse of the main mill building, and together they preserved it from demolition.

First, in 1930, the U. S. Post Office decided to develop a seaplane base in Charleston. After much discussion, the plan was discarded before any construction took place. City Council then leased the building and adjacent wharves to the American Bagging Company. Until 1936, that firm used the property as a storage depot for jute fiber imported for the Charleston Bagging and Manufacturing plant on Meeting Street (today’s Hampton Inn).

The mill building and adjacent Municipal Yacht Basin next became the heart of a notion even more improbable than a post office seaplane fleet: Charleston as the gateway for transatlantic flights between the United States and Germany. In January, 1937, work began on the "James F. Byrnes Trans-Atlantic Air Base."

To clear the West Point Rice Mill for renovation as an airline terminal, WPA laborers dismantled the interior, tossing out company papers and record books along with seventy-five year old construction material and industrial debris. The airport plan must have seemed realistic: Pan American Airways joined the project, bringing in the New York City architects Delano and Aldrich to collaborate with the local firm Simons and Lapham. By late 1939, the lower two levels of the building had been remodeled, and a road had been laid from Calhoun Street to the site. By that time, though, it was obvious that commercial air travel to war-torn Europe was impossible, and work was discontinued on the Charleston Passenger Station.

Instead of reuse as a seaplane terminal, in 1940 the West Point Rice Mill became offices for the Civilian Conservation Corps. When the CCC moved out in 1941, the third and fourth floors were finished, and officers of the Charleston Area Inshore Patrol, Sixth Naval District, moved in. The U. S. Navy constructed barracks, mess halls, warehouses, and recreation buildings at West Point, and used the property through the 1950s. The City of Charleston next leased it to the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, and in 1994, a private development firm signed a long-term lease on the West Point Rice Mill. The building was rehabilitated as restaurant/reception rooms with offices above.

Municipal Yacht Basin

The West Point Rice Mill is set on a sliver of high ground that was part of Daniel Cannon’s “South Mill” property. Cannon’s early nineteenth century sawmills and their successors relied on the tidal ponds that characterize the west side of Charleston. The basins were altered and improved by a series of lumber milling operations. The Municipal Yacht Basin began as a partial impoundment of a tidal pool.

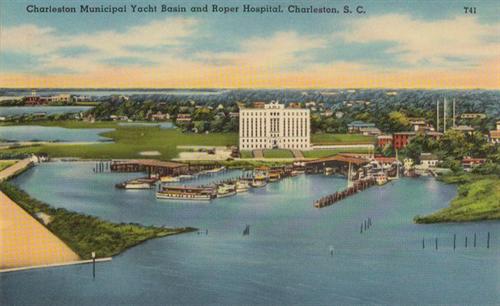

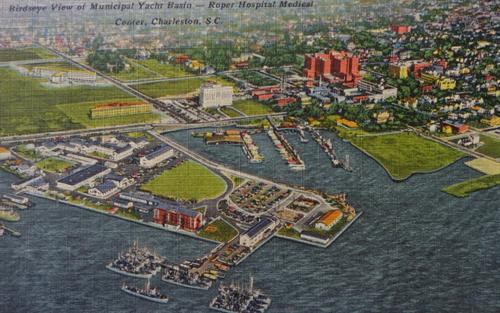

When New Deal agencies began funding harbor improvements in the early 1930s, Charleston benefitted from such projects as the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway and the upgrades of the West Point Rice Mill wharves for commercial shipping. Among the first projects of the Civil Works Administration (CWA) was to make over the last large mill pond as Charleston's Municipal Yacht Basin. Work began in December 1933, and the protected harborage was soon open for business. Tourism promoters extolled its potential for serving recreational traffic on the inland waterway, and the yacht basin was enlarged as part of the Trans-Atlantic Air Base project. Even during the Great Depression, many could still afford recreational boating. Between November 1937 and February 1938, about 200 transient vessels stopped in Charleston.

In 1942, the U. S. Coast Guard requested use of the yacht basin for the duration of the war; the lease was soon executed by City Council, with a small wharf and basin reserved for private and commercial boats. When Lockwood Boulevard cut off the Municipal Yacht Basin from the Ashley River in the early 1960s, the tidal pond became known as Alberta Long Lake. It is maintained today by the Parks Department of the City of Charleston.

"Destructive Conflagration! West Point Mill Destroyed." Charleston Mercury, November 14, 1860.

"Do You Know Your Charleston? Municipal Yacht Basin." News and Courier, June 6, 1938.

Halsey, Alfred O. "The Passing of a Great Forest and the History of the Mills Which Manufactured it into Lumber." Year Book, City of Charleston, 1937.

Historical Commission of the City of Charleston. "West Point Rice Mills." Year Book, City of Charleston, 1937.

Lapham, Samuel, Jr. "The Architectural Significance of the Rice Mills of Charleston, S. C." Architectural Record, July-December, 1924.

West Point Rice Mill. National Register nomination, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1994. http://www.nationalregister.sc.gov/charleston

West Point Rice Mill, 1940. |

West Point Rice Mill, 1940. |

West Point Rice Mill, 1849. |

West Point Rice Mill, 1864. |

West Point Rice Mill, 1872. |

West Point Rice Mill, 1877. |

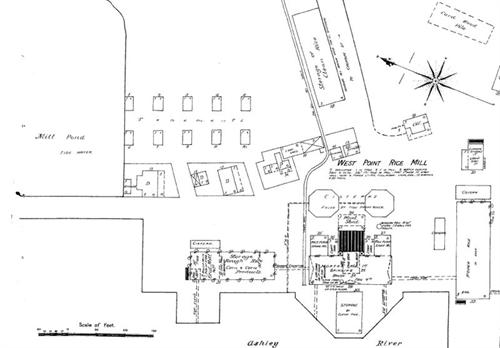

West Point Rice Mill, 1888. The main factory was surrounded by workers' quarters, a cooperage, wharves, a rough rice storehouse, a carpenter's shop, a small flour mill, and a blacksmith shop. |

West Point Mill and Ponds, 1931. |

Municipal Yacht Basin, facing north, early 1950s. The causeway at left was incorporated into Lockwood Boulevard after 1960. |

West Point Rice Mill and Yacht Basin. |

With the extension of Lockwood Drive from Calhoun Street to Broad Street, the Municipal Yacht Basin was replaced by today’s City Marina along the east bank of the Ashley River. The tidal pond became known as Alberta Long Lake. |

WestPoint1849_500x500.jpg)

1931MapForWestPointMill_500x500.jpg)