| The 1830s: A Decade of Fire |

|

||

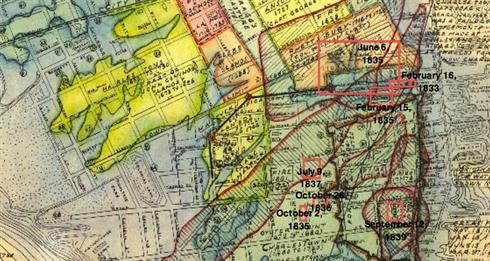

Fires of the 1830s. |

After a dangerous fire on December 24, 1825, which cleared the block bounded by South Battery, Lamboll, King, and Legare streets, and another that destroyed at least thirty buildings on King Street above Calhoun Street in June 1826, Charleston enjoyed a seven-year period without any serious fires. The mood was self-congratulatory: “Our city has fortunately, for a considerable period, escaped the effects of fire.” “In five years there has been but one house of value consumed by fire… Setting aside this single fire, we have the remarkable fact of a city composed of 35,000 inhabitants, including the suburbs, having sustained damage from conflagration in five years of only about $2600.”

The complacency was shattered at seven o’clock in the evening on February 16, 1833, when the fire alarm rang out. Near the northwest corner of East Bay and Market streets, a business owner had stumbled on the stairs of his rag and cotton storehouse while carrying a light.

Within about two hours, the area now occupied by the City Market sheds between East Bay and Anson streets was “entirely consumed.” The pork market burned, the wooden vegetable market was pulled down, and a corn warehouse was blown up to stop the fire from crossing Anson Street. About forty buildings were lost, “many of them [rental properties] not of much value, being occupied principally as small shops, eating houses, etc.; but the effects were the most distressing, from falling on a class of poor persons, several of whom have lost their all.”

The city market neighborhood was characterized by closely spaced buildings, rental occupancy, and lax oversight. Bakeries, cheap dwellings, storehouses and repair shops coexisted with taverns and “sailors’ boarding houses.” Just after midnight on February 15, 1835, a fire broke out in a brothel “of the very lowest and degraded character” at the north corner of State and Linguard streets. Soon, a dozen buildings were ablaze, the fire threatening to spread south across Amen [Cumberland] Street.

Mostly confined to the two city blocks between Market, Cumberland, Church and State streets, the fire’s great blow was the loss of St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, south of Cumberland Street. Windblown sparks ignited the domed top of the steeple, which “burned downward, then fell in with a crash which was succeeded by magnificent burst of fire from the tower, which continued for more than an hour to send up volumes of flame, until at last the body of the church and the whole roof kindled at once, and the destruction was complete.” The remains of the steeple and the front of the portico fell into Church Street the next morning. The entire city mourned the destruction of a building “unsurpassed in architectural beauty by any edifice in the Union.” More than a century old, the church had been saved from fire in 1796, and spared again in 1810 when the surrounding neighborhood burned.

A few buildings survived: Mr. Aiken’s brick range at the corner of Church and Market streets, four or five brick houses on State Street, and three wooden houses at the corner of Linguard and Church streets. At least sixty buildings were leveled or beyond repair, but the church and Mr. Lindley’s brick livery stables were the only costly buildings destroyed. As with the 1833 fire, the “loss has fallen chiefly upon very poor persons.”

Charleston was still recovering from February’s fire on June 6, 1835, when “one of the most awful and destructive conflagrations that has visited our city since the great fire of 1810” erupted. It began before dawn on the west side of Meeting Street, between Market and Hasell streets, in a small wooden building used as a saddlery. Flames jumped to the east side of Meeting Street, burned both sides of Hasell Street, and illuminated the night sky as a high wind drove the fire southward.

The roof of the beef market fronting on Meeting Street was badly damaged, the “fourth occasion on which within little more than two years our market has sustained injury – three times by fire and once by storm.” The range of sheds behind the beef market was consumed, as were nearly all the buildings on Ellery (North Market), Guignard, and Pinckney streets. Every building on the west side of Anson Street between Market and Pinckney streets was lost. Maiden Lane was burned out; firemen blew up Mrs. Thompson’s house in order to save Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church at the opposite corner of Maiden Lane and Hasell Street. However, St. Stephen’s Chapel on Guignard Street and the Baptist Lecture Room on Pinckney Street were both reduced to ashes.

The fire burned into the morning, more than eight hours altogether. Damage assessments began while exhausted firefighters battled the last blazes. The preliminary list of buildings burned, blown up, or pulled down comprised 182 dwelling houses and stores, and an estimated 374 outbuildings (allowing two per lot). This early estimate was probably low: four city blocks bounded by Meeting, Anson, Hasell, and Market streets had been leveled, leaving only Samuel Lord’s brick dwelling house in Maiden Lane, and the sugar refinery, a large brick building on the north side of Pinckney Street. (Neither building survived the next great fire, in April 1838.)

Most of the losses were wood-frame buildings; the financial toll to the owners was less important than the fate of their occupants, the “destitute and houseless poor who have neither home nor shelter.” As the Courier phrased it, “hundreds of individuals have been rendered homeless and houseless by this dreadful calamity.”

The fire was followed by a chorus of complaints about the city’s inability to prevent fires, and proposals for revitalizing the “burnt district.” During the summer of 1835, City Council bought most of the lots in the four-block area northeast of Meeting Street and the City Market. Newly paved and widened streets replaced narrow alleys, and the city aided the developers of two grand construction projects: a range of substantial masonry wholesale stores along the new Pearl Street [today’s Hayne Street], and the fine Charleston Hotel.

Fires continued with dreadful frequency, and there were two in a 24-hour period, October 2 and 3, 1835. Four buildings on the west side of King Street, between Broad and Tradd streets, were damaged beyond repair. The list of losses illustrates the mixed usage typical of antebellum Charleston: Mrs. Thompson’s dry goods store; Jacob Hertz’s wooden dwelling and dry goods store; a wooden dwelling and tailor shop owned by one Huger, a free colored man; and a double brick building, both halves occupied by dry goods merchants.

The next night, Mr. Stewart nearly lost his hotel on Broad Street, which he had “just fitted up in an elegant style.” A rear annex and the kitchen house burned, along with one of the stables owned by Mr. Frances at the east side of Church Street.

Another fire on October 26, 1836, destroyed five buildings at the south side of Broad Street between King and Meeting streets; and on March 23, 1837, the barque Commerce caught fire at Vanderhorst’s Wharf. Her hold packed with cotton for Liverpool, the vessel was heavily damaged, and local newsmen were certain that “an incendiary has been at work in the matter.”

Suspicions of arson had become as common as criticism of Charleston’s disorganized fire departments. After the huge fire of June 1835 (which some were convinced had been the work of a “base miscreant”) came a flurry of reports of attempted arson. Many believed the Stewart’s Hotel fire was deliberately set, and several men, white and black, were taken for questioning. Nothing definitive seems to have come of the investigation, and nothing was done to resolve the conflicting duties of the Board of Fire Masters, the volunteer companies, and the city pumping engine crews.

The firemen’s inadequate water supply led to increasing reliance on explosions, blowing buildings to rubble to reduce the height of the blaze. More property was lost to gunpowder than to flames during the July 9, 1837, fire, which began about 3:30 AM in a shed behind the Sutcliffe residence on the south side of Queen Street. Two buildings to the east, a clothing store and a two-story brick dwelling, were burned, and as the fire spread westward, it engulfed Henry Clark’s kitchen house. Several buildings were quickly blown up: Clark’s residence, three small dwellings, and Charles Green’s two-story wooden grocery and dwelling at the corner of King Street. Burning south along King, flames consumed two brick structures – a three-story tenement house and a print shop/residence. The fire was stopped by the demolition of the Quaker meeting house; by blowing up several other buildings, firemen prevented the flames from crossing north of Queen Street or west of King Street.

Several slaves hauling a fire engine through the dark streets were nearly killed by firefighters’ explosives. The Chief Engineer having ordered a house to be demolished, his men placed gunpowder inside, ignited the fuse, and sounded a horn to clear the area. Just then, a pumping engine “drawn by negroes and directed by the proper officer, came furiously down the street, burst through the crowd and rushed into the deserted spot. Amidst the noise and confusion, and the rumbling of the engine over the stones, the loudest cries were unheard or disregarded, and the poor fellows attached to the engine, full of zeal and energy moved on… The engine was halted directly in front of the building; the explosion instantly followed.” Although there were no immediate fatalities, two men belonging to William Bell were severely wounded. The disaster was caused by mismanagement, but it was the Charleston Mercury’s opinion that “there was obviously not the slightest blame to be attached to any one in this case. The occurrence was unavoidable, and originated entirely from the confusion which always prevails more or less at fires, and the honest zeal … that is utterly regardless of consequences.”

Faith in gunpowder was not shaken by the injuries inflicted on the unnamed slaves. On July 12, the Courier published Chief Engineer C. R. Holmes’s report to Mayor Robert Y. Hayne, which concluded with the advice that citizens not “permit the doors and window shutters of their dwellings to be taken off, or the sashes to be taken out, as it would be very difficult to blow up a house thus stripped, in the event of its becoming necessary to do so.”

The worst of the fires of the 1830s was the great fire of 1838, which destroyed nearly 150 acres at the heart of the commercial district. Rebuilding continued for several years, during which a number of fires were recorded in Charleston.

On the night of April 16, 1839, fire broke out in a wheelwright’s shop on King Street, spreading to adjoining properties and across the street. Firemen blew up or tore down a number of buildings in order to stop the blaze. On July 14, 1839, a dwelling and store kept by Mr. Heineman at 60 King Street (not the same parcel as today’s 60 King), were lost to fire.

Three wooden houses on Wall Street near Boundary [Calhoun] Street burned on August 7, 1839; one building was blown up, and a man killed by the explosion. “He was a laborer, and a native of Ireland, but his name is not given.” A fire that began at 2:30 AM on September 1, 1839, destroyed a range of buildings known as “the old Cross Keys” at the corner of King and Columbus streets, a lot belonging to the Estate of Ruggles. James Culbert’s grocery store and its contents were lost, together with the stable and outbuildings on the property.

An extensive fire September 12, 1839, started in the early morning in a vacant wooden building on Bedon’s Alley. Although it stopped short of the well-constructed brick buildings fronting Tradd Street, most of Bedon’s Alley and the frame corner buildings on Elliott Street, both of them used as grocery stores, were destroyed. On Elliott Street west of Bedon’s Alley, a paint store and several families were burned out of a three-story wooden building. Along the west side of Bedon’s was a mix of masonry and frame structures, all occupied by “colored persons.” The vacant house where the fire began, two brick buildings, and two small wooden houses all burned to the ground. At the east side of Bedon’s Alley, more substantial buildings were lost, four brick buildings of two or three stories, and one frame dwelling house.

Charleston’s last fire of the 1830s began about nine o’clock on the evening of December 27, 1839, in a building on Chalmers Street near Meeting Street. Four structures were lost, three to flames and one to the City Engineer’s explosives. Buildings housing G. W. Logan’s office, the offices of the Charleston Observer, and William Keenan, a well-known engraver, burned, as did Jane Wightman’s three-story brick residence. A small wooden building owned by Ms. Wightman and occupied by Mr. Douglass was blown up by firemen, and the fire was contained despite a brisk wind.

Charleston Daily Courier, Mercury, and Southern Patriot, various dates.

Crooks, Daniel J., Jr. Charleston is Burning. Two Centuries of Fire and Flames. Charleston: The History Press, 2009.

“Fires in Charleston.” Appendix to Faye’s Charleston Directory, 1840-41 (microfilm, S. C. History Room, Charleston County Public Library).

Pease, Jane H., and William H. Pease. "The Blood-Thirsty Tiger: Charleston and the Psychology of Fire." South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 79 (1978).