|

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/ |

|

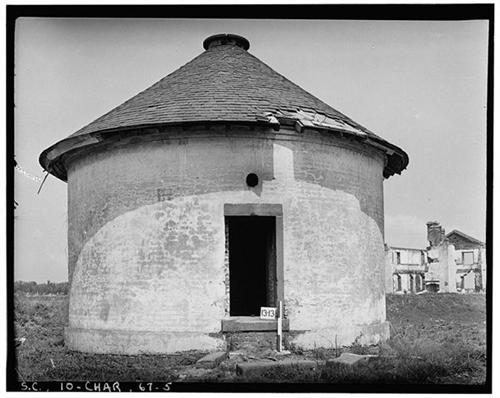

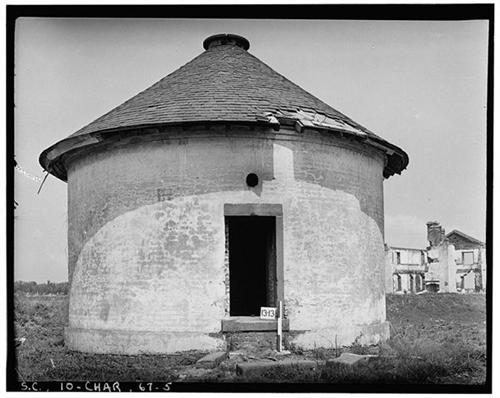

General view of the Powder Magazine complex, 1934 |

Between 1820 and 1823, architect Robert Mills (1781-1855) was employed by South Carolina's Board of Public Works, first as Acting Commissioner, then as Superintendent of Public Buildings. For several years afterward, he continued to work for the board as an independent contractor. During his tenure with the Board, Mills designed the Fireproof Building (South Carolina Historical Society, 100 Meeting Street), an addition to the Charleston Jail (American College of the Building Arts, 21 Magazine Street), and a complex of nine powder magazines, with a barracks/gatehouse, in the marshes of the Cooper River off Charleston Neck.

Beginning with the Old Powder Magazine, built in the early eighteenth century, public officials erected a series of gunpowder storehouses in and around Charleston. Magazines were built on public land near the Workhouse and Jail in 1737 and 1748; and at Shipyard Creek (Charleston Neck) and Hobcaw Point (Mount Pleasant) in 1772. In 1820, the Shipyard magazine was in such unstable condition that the city was forced to reopen the original magazine on Cumberland Street.

The next year, the Board of Public Works finally appropriated $8,000 toward the construction of secure arsenals in the Charleston area. On the Board's behalf, Mills purchased Laurel Island, five acres of high ground south of New Market Creek, from Mrs. Anne Langstaff. Laurel Island was part of a suburban plantation known as Bachelor’s Hall when it was owned by colonial governor Thomas Boone.

The new location was much preferable to the Shipyard Creek magazine being replaced. Even at low tide, New Market Creek was navigable to the site, making it acceptable to ship's masters; the city was visible from the residence of the keeper, who could thus signal as necessary; and the State Magazines on Laurel Island would be protected by the Neck guard.

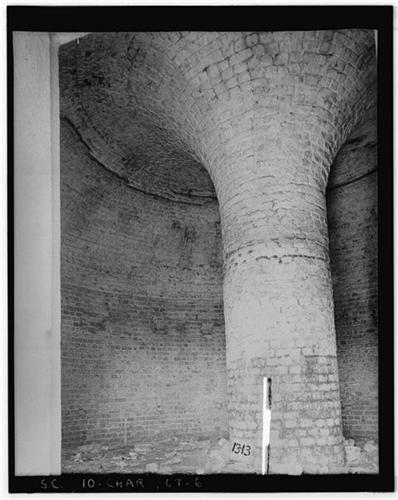

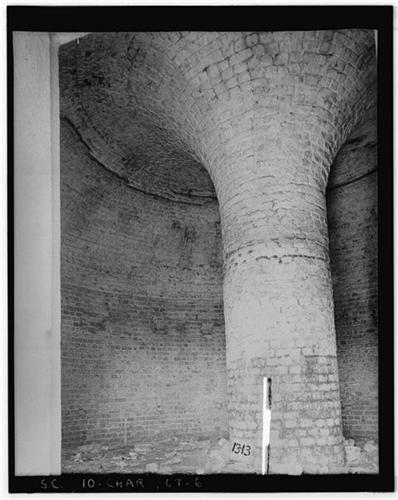

Construction was underway by the end of 1822. The magazine complex had nine circular buildings. A large magazine twenty feet in diameter, structurally supported by a column carrying the vaulted ceiling, could store four thousand kegs of publicly-owned gunpowder; the smaller magazines, each with a capacity of one thousand kegs, were assigned to different importers of powder. Mills himself noted that the "advantage of this arrangement will be that every importer of powder will have his own magazine, and in case of any accident to one the rest will be secure from explosion."

The magazines had thick brick masonry walls coated with rough-cast stucco, brownstone lintels and sills at the entries, and conical slated roofs. The gatehouse was a two-story barracks for guards built around an arched "grand gateway leading into the magazine court" where the magazines sat in three rows 130' apart.

Tensions were constant between those who wanted gunpowder readily accessible in Charleston, and those who feared its proximity. In 1851, while South Carolina's Governor and Legislature urged the use of magazines in the wings of the Citadel, City Council was loudly opposed, because "the erection of a powder magazine within the City of Charleston will be not only dangerous to the lives of the citizens, but will materially impair the value of real estate in the vicinity of the magazine from the fact that, in the event of the alarm of fire being given in that neighborhood, the firemen would not be willing to venture there, consequently the owners of property could not obtain insurance on their property as in other parts of the city."

The magazines remained on Laurel Island. In 1872, the state-owned land and buildings, described as thirteen acres, was sold to City Council of Charleston. The city rented the nine magazines to the E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co. for storage of dynamite and "black keg powder," then conveyed part of the property to Seaboard Air Line Railway in 1915. The railroad company tore down two of the magazines in order to lay track to Union Station downtown. The remaining seven magazines were demolished in the 1940s. Behre, Robert. "Mills' lost magazines. Little evidence remains of military facility." The Post and Courier, February 1, 2010.

Bryan, John M. America's First Architect, Robert Mills. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001.

Davis, Nora M. "Public Powder Magazines at Charleston." Year Book, City of Charleston, 1942.

"Do You Know Your Charleston? Powder Magazines of 1812." News and Courier, March 19, 1934.

Ravenel, Beatrice St. Julien. Architects of Charleston. Charleston: Carolina Art Association, 1945. 2nd ed., 1964.

|

|

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/ |

One of the eight smaller magazines seen with barracks in right rear of photograph, April 1934.

|

|

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress |

Interior column, public magazine, 1934

|

|

| McCrady Plats, #4076, S. C. History Room, Charleston County Public Library |

Surveyor Robert W. Payne showed the State Arsenal on his April, 1853, “Plan of Cool Blow Village and the Adjoining Marsh Belonging to Josiah S. Payne.”

|

|

| US Department of Commerce, Coast and Geodetic Survey, “Charleston Harbor, 1865.” American Memory, Library of Congress www.memory.loc.gov |

State Arsenal, 1865

|

| |

Map of Charleston, South Carolina, 1877 (detail). The State Arsenal site is just south of New Market Creek.

|

|

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress |

Site plan of seven magazines remaining in April, 1934.

|

|