The mid-September, 1752, cyclone was "the most violent and terrible hurricane that ever was felt in this province." Strong winds began the evening of September 14, becoming more violent as the storm blew closer. Rain sluiced down steadily through the early morning, and a terrifying night gave way to a horrifying day. The storm surge poured in about 9:00 AM, overflowing seawalls and creek beds. Before 11 o'clock, nearly all the vessels in Charleston Harbor were on shore, some driven into the marsh, some riding the flood to crash into wharves and buildings. A ship blew up Vanderhorst’s Creek as far as Meeting Street, carrying away a corner of the “new Baptist house” near the creek. Only the HMS Hornet, a fourteen-gun sloop of war, rode out the storm. Water had risen more than ten feet above the normal high-water mark, the sea covering the entire peninsula, and high tide was not expected for another two hours. With many houses flooded neck deep, panicked people fled to the upper floors and "contemplated a speedy termination of their lives." Their reprieve was deemed an act of Providence. The wind shifted, the tide ebbed, and the water flowed out as quickly as it had come in (the South-Carolina Gazette reported it fell five feet in ten minutes). By three o'clock Friday afternoon, September 15, the wind had died completely and the storm was gone. The hurricane "reduced this Town to a very melancholy situation." Although there are no accurate figures of the deaths or injuries, many drowned; others were killed or dangerously injured when houses fell apart. An estimated five hundred buildings were destroyed completely; broken chimneys, lost roofing tiles and slates, shattered windows, and dislodged foundations were universal. All the wharves and piers were smashed, every building upon them beaten down and carried away. Likewise, fortifications along the waterfront sustained heavy damage, most of their cannon dismounted. Granville's Bastion was "much shaken, the upper part of the wall beat in, the platform with the guns upon it floated partly over the wall." Craven’s Bastion was flooded, and surveyor general George Hunter reported a great loss: the cases containing “all the original warrants of survey, duplicates of plats and books of records … were overset and burst open, floating about in four and a half feet salt water, and are thereby much injured and defaced and some lost…” Not two weeks later, on September 30, another strong cyclone blew through the Lowcountry. It passed through Charleston in only a few hours, but ruined crops and livestock through the region. With the threat of winter food shortages, the government set tight limits on exporting "corn, pease and small rice" to ensure moderate prices on essential provisions. Bates, Susan Baldwin, and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds. Proprietary Records of South Carolina. Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of The Province, Charles Towne, 1678-1698. Charleston: History Press, 2007.

Fraser, Walter J., Jr. Lowcountry Hurricanes. Three Centuries of Storms at Sea and Ashore. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2006.

Rubillo, Tom. Hurricane Destruction in South Carolina: Hell and High Water. Charleston: The History Press, 2006.

South-Carolina Gazette, September 19, 1752.

|

|

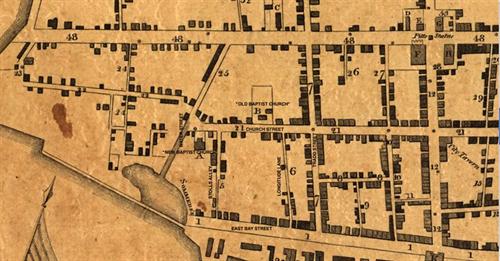

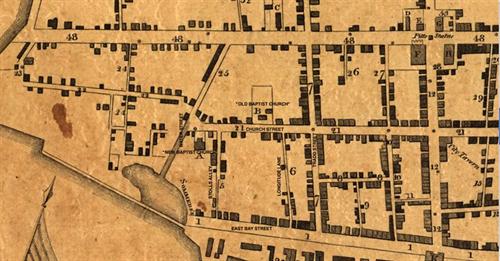

| Edmund Petrie, Ichnography of Charleston, South Carolina. London, Phoenix Fire Company, 1788. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

The new Baptist Church was built in 1746, when Charleston’s Baptist congregation split. In 1757 William Mason opened a school in the building, it was used by Methodist groups during the late eighteenth century, and in about 1820 the Marine Bible Society bought the property.

|

|

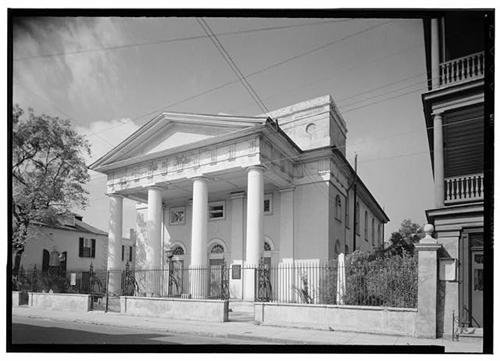

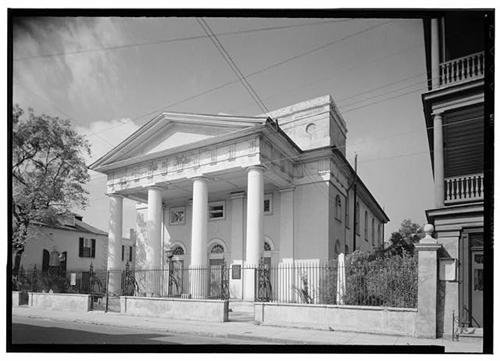

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress http://loc.gov/ |

In 1699 William Elliott, planter and member of the “People of ye Church of Christ Baptised on Profession of faith Distinguished from all other Churches by the name of Antipaedobaptist,” gave Town Lot 62 to trustees of the church for building a place of worship. The congregation has remained here since that date.

1940 view of First Baptist Church, 61 Church Street. Cornerstone laid 1819, building dedicated January 1822. Its architect, Robert Mills, considered it the “best specimen of correct taste in architecture of all the modern buildings in this city.”

|

1849 Baptist Churches_500x500.jpg) |

| W. Williams, “Plan of Charleston. S. C.” 1849. Courtesy of Alabama Maps http://alabamamaps.ua.edu |

First Baptist Church and Mariners Chapel, 1849.

|

|

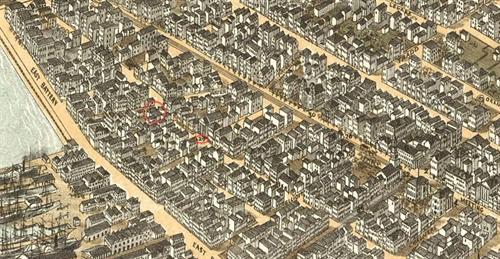

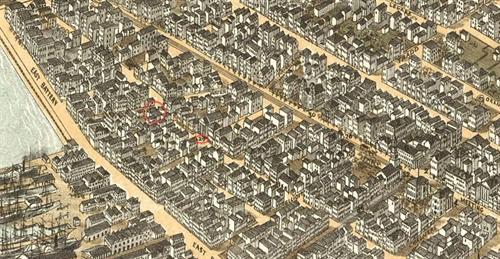

| C. Drie. Bird's Eye View of the City of Charleston, South Carolina. 1872. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

Mariners Church (28) and First Baptist Church (29). The Charleston Port Society for Promoting the Gospel among Seamen had taken over the “Mariners Chapel” and added a brick wing to the early building.

|

MK 82a_500x500.jpg) |

| MK82a Courtesy of The Charleston Museum www.charlestonmuseum.org |

Cook's Earthquake Views of Charleston and Vicinity. Taken after the 31st of August, 1886. No.150, Mariner's Church, exterior.

|

|

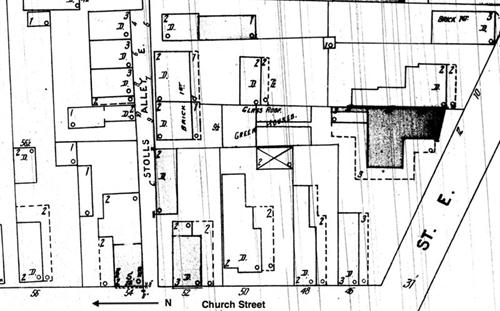

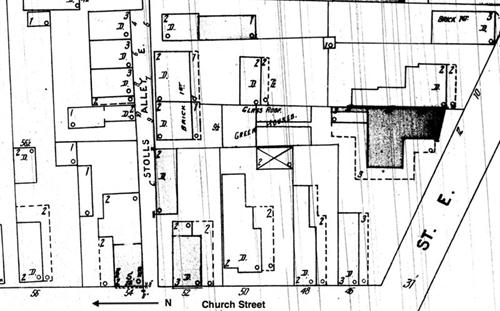

| Sanborn Map Company, 1902 |

Not long after the 1886 earthquake, the Mariners Chapel was replaced by a private residence, today’s 50 Church Street. In about 1916, the Charleston Port Society built the Church of the Redeemer at today’s 34 North Market Street, a location easily visible from commercial vessels tied up along the Cooper River waterfront.

|

Postcard view, “Church of the Redeemer and Harriet Pinckney Home for Seamen, East Bay and Market Street, Charleston, S. C.”

|

|

1849 Baptist Churches_500x500.jpg)

MK 82a_500x500.jpg)