|

| Edward Crisp, “A Compleat Description of the Province of Carolina in 3 parts.” 1711. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

|

The 1711 Crisp Map shows Vanderhorst’s Creek (M), Granville Bastion (A) and Ashley Bastion (E) connected by a palisade across the narrow tributary, and Colleton Bastion (D) north of Meeting Street.

|

The original plan for Charles Towne laid out a grid of streets and building lots on the peninsula. Salt-water creeks and marshes cut into several areas of the planned town. Two deep tidal creeks ran inland from the Cooper River, Daniel’s Creek and Vanderhorst’s Creek. Known since the late eighteenth century as Water Street, Vanderhorst’s Creek separated Church Street from White Point, the southern tip of the peninsula. It flowed across Meeting Street and extended beyond the west side of King Street. Smaller streams drained into Vanderhorst’s Creek from both sides. The shallow south branch was controlled as a tidal basin by the early eighteenth century, but the long arm that ran northward between Church and East Bay streets remained an open creek until the mid-1750s. In the early eighteenth century, a belt of protective fortifications enclosed the Charles Towne settlement. The southernmost wall was placed inland of Vanderhorst’s Creek, and featured bastions at each end: Colleton’s Bastion to the west and Ashley’s Bastion to the east. As the city grew, the earthen walls along Vanderhorst’s Creek and Meeting Street were abandoned and dismanteled. During the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739-1748), fears of an attack on Charleston led to another system of defenses, which relied heavily on earth and wood construction. The great hurricane of 1752 wrecked those walls and fortifications. Charleston’s defenses were rebuilt between 1755 and 1757, with new works designed by German military engineer Major de Brahm for Charleston’s Commissioners of Fortifications. In May, 1756, de Brahm ordered the line between Granville’s Bastion and Broughton’s Battery to be built level with the height of the “Flood-Gate newly constructed.” Under the roadbed of today’s East Battery, this floodgate managed the tidal flow into Vanderhorst’s Creek, controlling the stream as a thirty-foot wide channel deep enough for boats. For at least part of its length, the creek was lined with brick walls. With Vanderhorst’s Creek confined, property owners were encouraged to fill the tributary creek between Church Street and East Bay Street. As the block south of Tradd Street developed, two small east-west footpaths became established alleys, Longitude Lane and Stoll’s Alley. From the mid-1780s into the nineteenth century, Charleston’s political leaders engaged in a difficult effort to extend East Bay Street south to the tip of the peninsula. The work eventually led to the conversion of Vanderhorst’s Creek into Water Street. A legislative act and corresponding city ordinance in the spring of 1785 authorized City Council to continue East Bay Street “from its present termination to the extremity of White Point.” The work was to be funded by assessments on real estate, but property owners resisted paying. A series of acts and ordinances followed, each changing the mode of assessment slightly and all causing controversy. There had been little progress on the new street by 1788, when City Council appointed new commissioners for “completing East Bay Street to Ashley River, and for securing the east part of White Point from the sea.” The commissioners were to fund and build “a street of the same width of the southern part of East Bay Street … from the present termination of the said street until it intersects with the southeast angle of the fort …. and to make a good and sufficient front of palmetto and pine logs for the said street from the sea, of the same width of that begun by the late commissioners.” As late as December, 1795, the legislature was wrestling with how to collect payments, and hearing petitions from citizens claiming losses by the road’s being continued through their lots. Finally, in order to complete the work, in October 1798 City Council approved a special three-year tax assessment to cover funds already spent, and agreed to raise an additional $6,000 through a lottery. The financial challenges were compounded by the costs of repairs after two severe storms. On October 4, 1800, “as tremendous and destructive a storm was experienced in this city and harbor, as has happened for nearly 20 years.” Most of East Bay Street, “which was nearly completed and cost an immense sum of money, is destroyed.” The seawall and street were repaired, only to be wrecked again by the 1804 hurricane. New East Bay Street was “destroyed: the sea made clear breaches through it and rushing into Water Street and the adjacent parts, compelled the inhabitants to quit their houses…. The whole of Water Street was covered, and in Meeting Street it was nearly two feet in depth.” Water Street had been created gradually. Sometime after the Revolution, Vanderhorst’s Creek/canal was filled between Meeting and Church streets. By about 1784 it was known as Water Street. The east block, below Church Street, was finished more slowly. A 1798 plat of the Somers property (43 East Bay Street) depicts Water Street, and marks the area north of the street “shoal land dry at low water.” Only after final construction of East Bay Street and the seawall in the early nineteenth century was Water Street dry at high tide. Carolina Gazette, October 9, 1800

Charleston Times September 10, 1804.

City Gazette November 14, 1804 Bates, Susan Baldwin, and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds. Proprietary Records of South Carolina. Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of The Province, Charles Towne, 1678-1698. Charleston: History Press, 2007.

Burton, Milby. “Water Street,” in unpublished two-volume typescript “Streets of Charleston.”

Butler, Nic. “Charleston’s Earthen Entrenchments, 1703-1734.” Rediscovering Charleston’s Colonial Fortifications. http://walledcitytaskforce.org

Ordinances 24, 52, and 166 in Edwards, Alexander. Ordinances of the City Council of Charleston, In the State of South Carolina, Passed since the Incorporation of the City, Collected and Revised Pursuant to a Resolution of the Council…. Charleston, 1802. www.google.books.com

Fraser, Charles. Reminiscences of Charleston. Charleston, 1854. http://books.google.com

Acts 1359, 1442, and 1629 in McCord, David J., ed. The Statutes At Large of South Carolina. Vol. 7, Acts Relating to Charleston, Courts, Slaves, and Rivers. Columbia, 1840. www.googlebooks.com

Act 1282 in McCord, David J., ed. The Statutes At Large of South Carolina. Vol. 9, Acts Relating to Roads, Bridges and Ferries. Columbia, 1841. www.googlebooks.com

Alice R. Huger Smith and D. E. Huger Smith, The Dwelling Houses of Charleston, 1917. http://books.google.com

Stockton, Robert P. “Discovery unlikely part of walled city.” Letter to the Editor, The Post and Courier, September 19, 2006.

|

1680Creek_500x500.jpg) |

| Henry A. M. Smith, “A Platt of Charles Town.” South Carolina Historical Magazine, 1908 (copy in City Engineer’s Plat Book, S. C. History Room, Charleston County Public Library) |

A twentieth-century reconstruction of Charleston’s original plan shows Vanderhorst’s Creek and its branches. Church Street terminated at the creek.

|

ColletonBastion_500x500.jpg) |

| Preservation Society of Charleston |

|

1739AnnotatedForVanderhorst Creek_500x500.png) |

| Bishop Roberts and W. H. Toms, The Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water. London, 1739. |

In 1739, development of the block between Church, East Bay, and Tradd streets was impeded by a tidal creek and marsh. The southward extension of Church Street was first proposed in 1736, and relied on a bridge to John Vanderhorst’s settlement.

|

Creek1780FrenchMap_500x500.jpg) |

| Plan de la ville de Charlestown, de ses retranchements et du siege faits par les Anglois en 1780. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

In 1780, Vanderhorst Creek was controlled as a tidal canal. After being burned out by fire in 1778, merchant James Witter, Jr., moved his business to the "house where he lives in Church Street, opposite Stoll's Alley and near Young's Bridge, being very convenient to land indigo." Vanderhorst’s Bridge became known as Young’s Bridge sometime after 1769, when Thomas Young bought a parcel of land from the heirs of John Vanderhorst.

|

1788WaterStreet_500x500.jpg) |

| Edmund Petrie, Ichnography of Charleston, South Carolina. London, Phoenix Fire Company, 1788. American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

By 1788, Water Street had replaced Vanderhorst’s Creek between Church and Meeting streets. East of Young’s Bridge, the creek remained a tidal canal.

|

Creek1833TannerInset_500x500.jpg) |

| Henry S. Tanner, “A New Map of South Carolina with its Canals, Roads and Distances from Place to Place along the State and Steamboat Routes.” Ca. 1833 American Memory, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/ |

Water Street, 1833.

|

|

| McCrady Plat #3332, Charleston County RMC (microfilm copy, Charleston County Public Library, SC History Room) |

E. B. White’s 1842 plat shows development in the block between Water and Atlantic streets (the Ravenel House, today’s 31 East Battery, had been built by 1840, but it was not part of the tract being surveyed.)

|

|

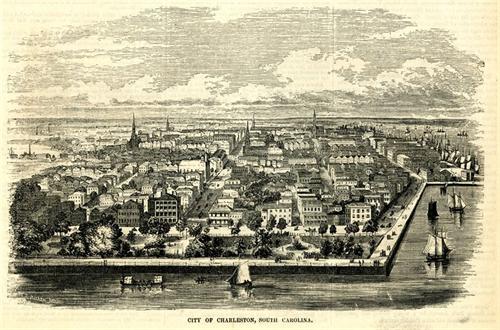

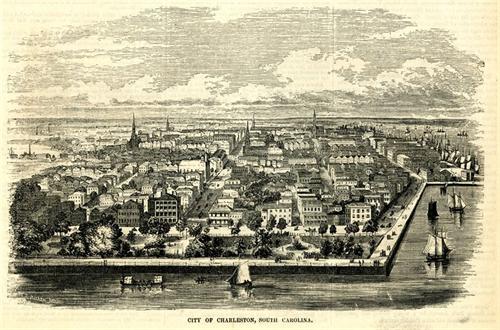

| Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion |

This 1855 view of Charleston from the south shows East Bay Street extension (East Battery) and East Bay Street.

|

43EastBay_500x500.jpg) |

| Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print |

43 East Bay Street in 1937.

George Sommers’ ca. 1775 residence was built at the end of East Bay Street, on property that bounded south “partly on the brick wall and partly on a small wooden bridge leading to the westward.”

|

AlongEastBay_500x500.jpg) |

| private collection |

“Along East Bay at Stolls Alley.” Early 20th century postcard view shows 43 East Bay, 45 East Bay, 47 East Bay, and 51 East Bay Street.

|

31EastBattHABS_500x500.jpg) |

| Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov |

Charles Fraser (born in 1782): “I have often, when a boy, swum through a brick flood-gate next to where Mr. Daniel Ravenel’s house now stands. … This flood-gate had, no doubt been placed there to prevent the encroachments of the sea, and give safety to the fishing boats, which I remember seeing there in great numbers.”

Ravenel’s house at 31 East Battery was later the residence of George D. Bryan, mayor of Charleston from 1887-1891.

|

|

1680Creek_500x500.jpg)

ColletonBastion_500x500.jpg)

1739AnnotatedForVanderhorst Creek_500x500.png)

Creek1780FrenchMap_500x500.jpg)

1788WaterStreet_500x500.jpg)

Creek1833TannerInset_500x500.jpg)

43EastBay_500x500.jpg)

AlongEastBay_500x500.jpg)

31EastBattHABS_500x500.jpg)