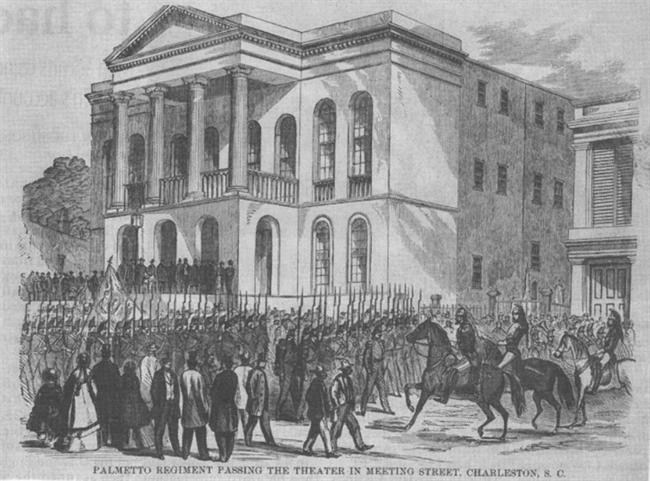

45. New Theatre 1837

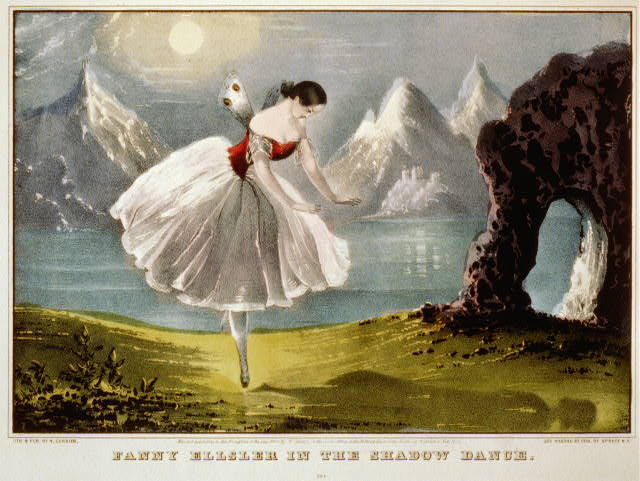

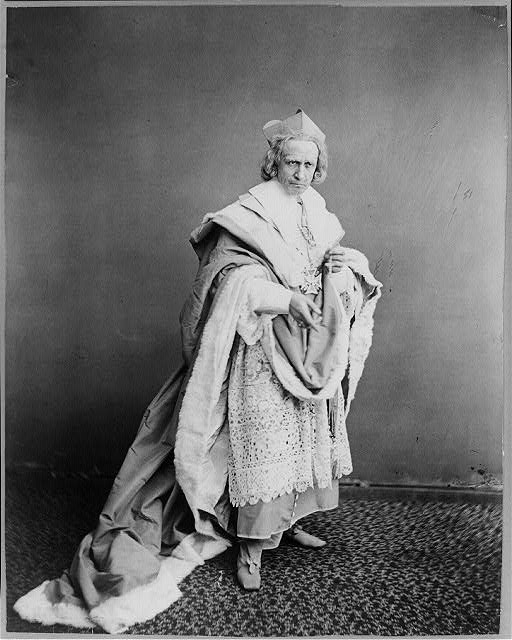

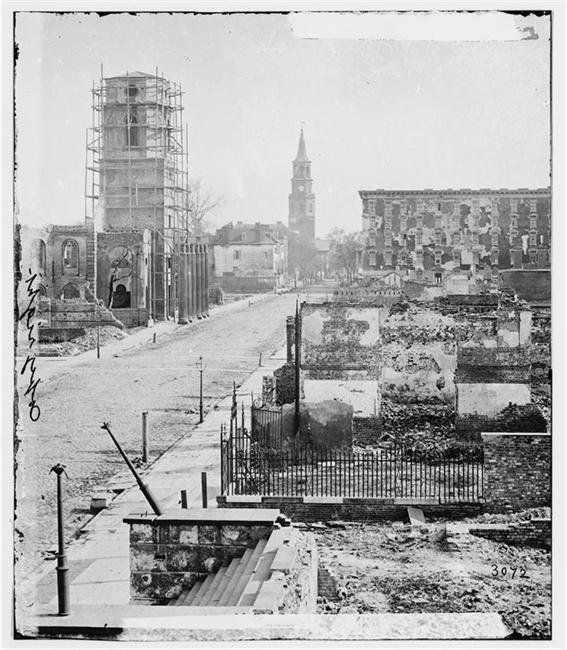

After Charleston's only purpose-built playhouse, the Broad Street theater, closed in 1832, the city was without a proper theatrical venue. Visiting performers, even the international star Tyrone Power, had to mount their productions in the revamped circus amphitheatre north of the old Vauxhall Garden. In early 1835 a group of businessmen led by Robert Witherspoon agreed to develop a new theater enterprise, promoting it as a civic improvement. They bought a lot on Meeting Street from the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free Masons of South Carolina, and organized "The Charleston New Theatre," as a joint-stock company. Local interest was high, and the managing partners engaged prominent architect Charles Reichardt to design a world-class auditorium, which was erected by a partnership of builders, Curtis, Fogartie and Sutton. While construction was underway, the 1,200-seat theater was leased to an experienced actor-manager who brought a company of players to Charleston. The New Theatre was described at length in contemporary newspapers (see Charleston Courier, December 18, 1837). Two full stories in height above a raised basement, the stuccoed brick building had a massive Ionic portico, with four columns, above an arcaded base. The portico was accessible only from within the building; entry from Meeting Street was through the arcade level. Three main doors opened to the lobby/vestibule, which had a ticket office at one side, ladies withdrawing room at the other, and a corridor leading to the boxes and seating floor. Above the richly ornamented auditorium was a large dome, at its center a forty-eight lamp chandelier eight feet across. A large audience attended Charleston's new theatre on its opening night, December 15, 1837. After Mr. Latham delivered a "poetical address" written for the occasion by William Gilmore Simms, theater manager William Abbott took the lead role in the play, The Honey Moon, supported by Miss Melton and Mrs. Herbert, who also sang an "afterpiece." A few months later, Abbott booked Junius Booth, advertising in March, 1838, that the "eminent Tragedian," would make his first appearance in Charleston in more than a decade. Booth's characterization of Sir Giles Overreach was, as always, well received, the Southern Patriot's reviewer excitedly declaring it "among the finest exhibitions of histrionic power we have ever witnessed… On the whole it was the most thrilling piece of acting we have ever seen…" In May, 1840, the celebrated German ballerina Fanny Elssler, whose appearances in Baltimore and New York had caused riots among her adoring fans, danced at Charleston's theater. Although Abbott left Charleston in 1841, a series of managers ran the theater more or less successfully for the next twenty years. G. F. Marchant was the lessee in 1858 and 1859 when Edwin Booth (son of Junius Booth, and brother of John Wilkes Booth) played several engagements, reprising his father's great roles as Richelieu, Hamlet, Giles Overreach, and Othello. McInnis, Maurie D. The Politics of Taste in Antebellum Charleston. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

|