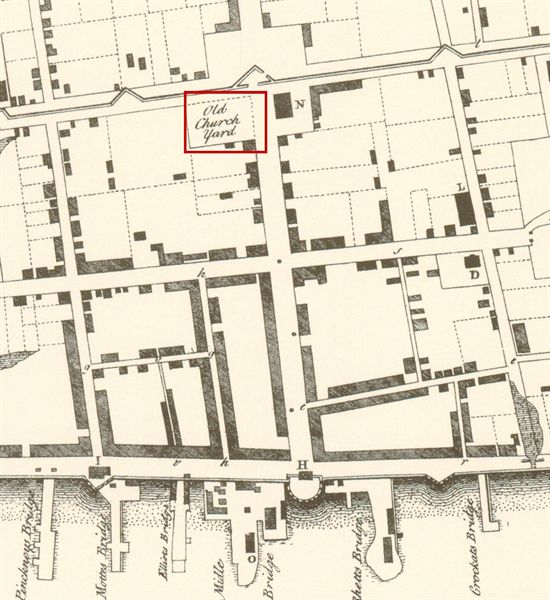

The first church on the southeast corner of Broad and Meeting Streets was St. Philip's Church, whose small building, constructed of black cypress on a brick foundation, occupied this site from circa 1683 to 1723. As Charles Towne's population grew, a larger Anglican church was required, and construction began on the second St. Philip’s Church, in 1712. That building, on today's Church Street north of Queen Street, was completed in 1723. The original church was then abandoned, and taken down in 1733. Because there were many burials in the churchyard, the lot at the corner of Broad and Meeting streets was not redeveloped for secular use.

In 1751, the Commons House of Assembly divided Charles Towne into two Anglican parishes. The part of town south of Broad Street became the new parish of St. Michael's; north of Broad Street remained St. Philip's Parish. In 1751, royal governor James Glen approved legislation calling for a new church to be built on the same corner as the old St. Philip's Church, and on February 17, 1752, he laid the cornerstone. The spire was begun in the summer of 1753, then construction funding was stalled because of concerns about the coming war between Great Britain and France (French and Indian War, 1754-1763). Piecemeal public funding allowed gradual progress during the next few years, with final completion in 1761.

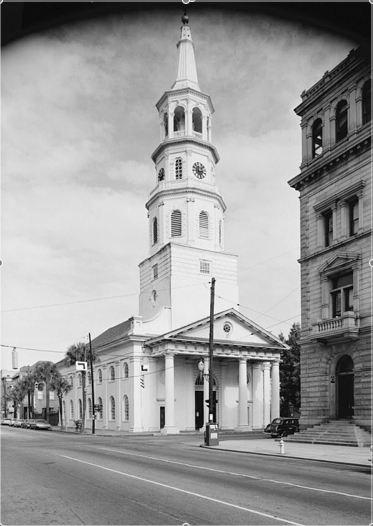

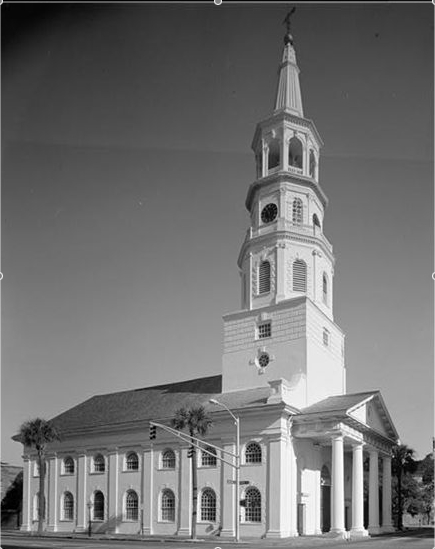

St. Michael's Episcopal Church is the earliest extant church building in Charleston and one of the finest Neoclassical-design churches in the United States. Although the architect is unknown, the building bears strong similarities to St. Martin-in-the-Fields in London, designed by James Gibbs and illustrated in his 1728 pattern book, A Book of Architecture. The final design resulted from decisions made by the fifteen-man commission appointed to erect the church, and by its builder, Samuel Cardy.

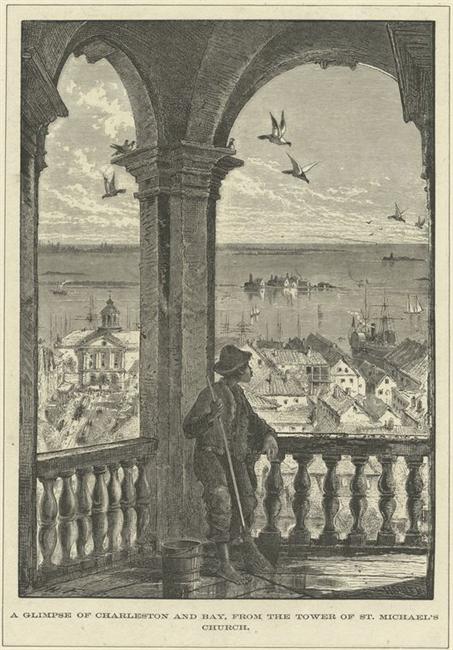

Since opening for services on February 1, 1761, the building has survived multiple natural disasters and battles. The tower has served as both a defense and a fire-lookout for most of its history. The spire was painted black during the American Revolution in an attempt to hide it from British gunners. The British declared that it made it more conspicuous and on April 16, 1780, it was struck by a shell. The chancel was destroyed during the 1864 Union bombardment of the city, when it was struck from Morris Island. The bells were taken to Columbia for safekeeping during the Civil War but ruined when Sherman burned the city.

St. Michael's Church has been effectively restored numerous times since it was constructed over two centuries ago. It remains an icon on Charleston's original public square.

Nelson, Louis P. The Beauty of Holiness. Anglicanism and Architecture in Colonial South Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Waddell, Gene. Charleston Architecture, 1670-1860. Vol. 1. Charleston: Wyrick and Company, 2003.

Williams, George W. St. Michael's Charleston 1751-1951, With Supplements 1951-2001. College of Charleston Library, 2001.

_650x650.jpg)

StMikesPostcard_650x650.JPG)