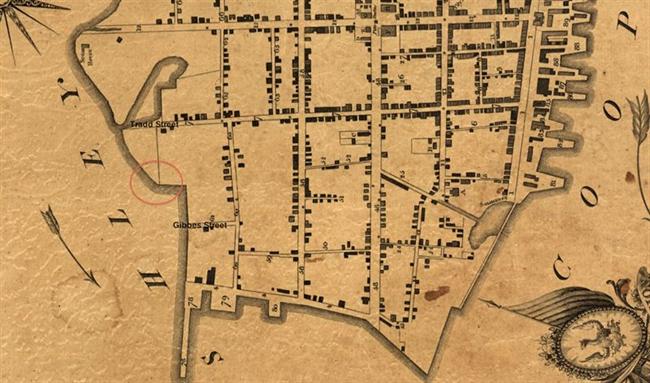

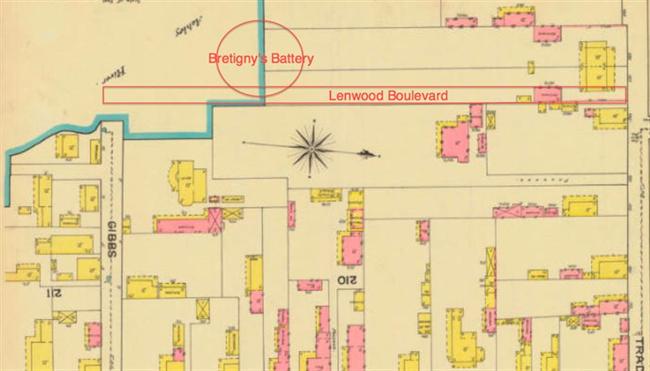

Bretigny's Battery, near the west end of today's Gibbes Street, was named in honor of the Marquis de Bretigny, commander of the French battalion of militiamen in Charleston. Part of a belt of waterfront fortifications "formed of earth and palmetto wood, judiciously placed and mounted with heavy cannon,” the battery was generally known as Ferguson's, for its location near Thomas Ferguson's residence.

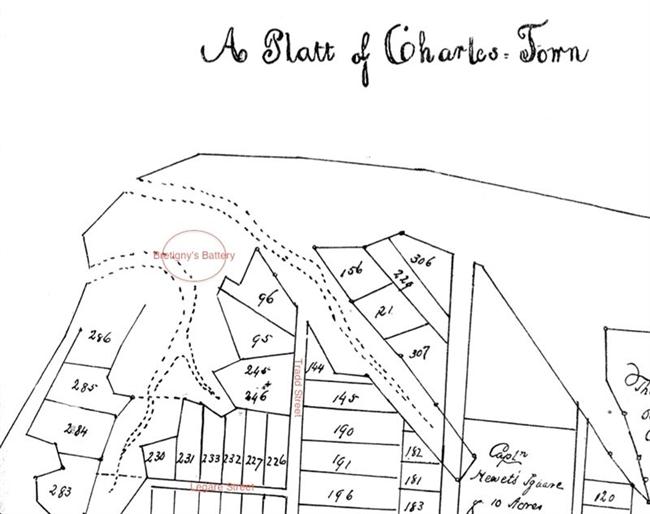

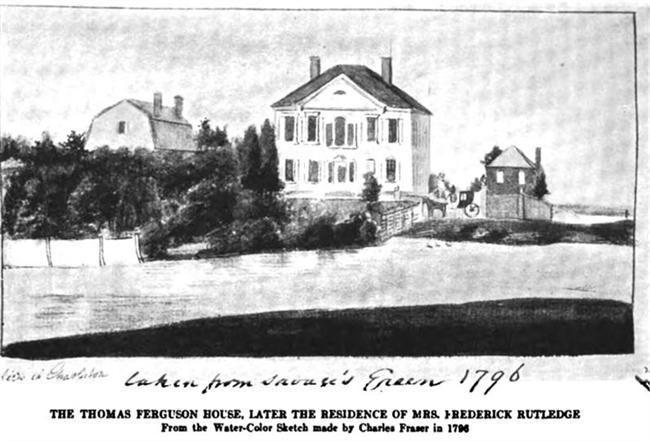

The Ferguson house stood on part of a large tract that the Estate of Benjamin de la Conseillere had sold to Thomas Shubrick in about 1754. Between the two arms of Conseillere’s Creek, the parcel comprised Town Lots 95, 96, 245, and 246, together with six adjoining acres of "sand beach or shoal.” When Shubrick sold the land a few years later, he praised the advantages of upper Tradd Street: "a most beautiful situation and prospect, being so open to the refreshing south, southwest, and westerly breezes, that no summer day or night is troublesome." The open exposure that made the area so healthy also made Ferguson’s waterfront lot suitable for a defensive fortification.

Between February and April 1780, while Charleston awaited the inevitable British attack, public works managers improved the defensive line facing the Ashley River. From Ferguson's beach northward to within about two hundred yards of Cummins Point Battery, they slogged through the marsh, ditching and diking to make the creeks impassable for small craft. By the time the siege began in earnest, guns were mounted in Ferguson's battery.

Riverfront batteries were intended to damage British warships and prevent their men from landing on the peninsula. They could not repel fire; on the contrary, they were targets and nearby buildings suffered collateral damage. A cannonball fired from the British battery at the mouth of Wappoo Creek [Fenwick's Point] struck Thomas Ferguson's house, passing "between two iron balusters of a balcony, bending them outward, and went on its way. The balusters were never straightened, and all children were told the tale." One of these children was Harriott Horry Rutledge, whose grandparents bought the Ferguson house in 1798. The house was destroyed by the great fire of December, 1861.

Borick, Carl P. A Gallant Defense, The Siege of Charleston, 1780. University of South Carolina Press, 2003.

DeSaussure, Wilmot G. "An Account of the Siege of Charleston, South Carolina, in 1780." City of Charleston Yearbook, 1884.

Gordon, John W. South Carolina and the American Revolution, A Battlefield History. University of South Carolina Press, 2003.

Moultrie, William. "A Return of the Number of Cannon &c. in Charlestown, at the Surrender, on the Twelfth of May, 1780, in the Batteries." Memoirs of the American Revolution. New York, 1802; rep. ed. Arno Press, 1968.

"The Siege of Charleston, 1780." Appendix to City of Charleston Yearbook, 1897.

Ravenel, Mrs. St. Julien (Harriott Horry Rutledge). Charleston. The Place and the People. MacMillan Company, 1912; rep. ed. Southern Historical Press, 1972.

Britigney_sBattery1780_650x650.png)