Governors Bridge carried East Bay Street across a tidal creek at the north side of Charles Towne. The bridge had been completed by 1747, when Charles Pinckney paid for construction material “agreed to be landed at the new bridge.”

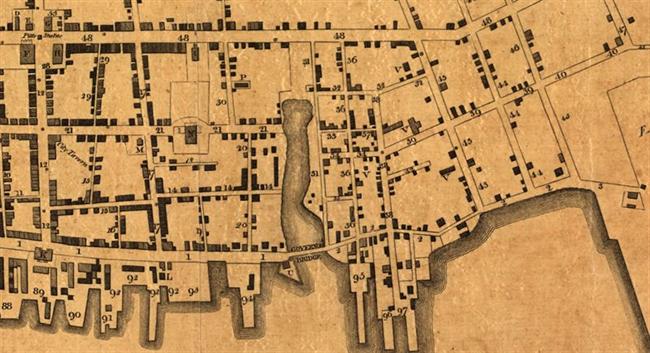

When Charleston was settled, this creek and its marsh spread inland from the Cooper River as far west as Meeting Street. “Major Daniel’s Creek” was maintained as a shipping channel, with ongoing improvements that drained wetlands as “made ground” for building lots. After the bridge closed off its upper reaches, the creek was filled as Canal or Ellery street – today’s North Market Street.

In 1747, when the bridge was new, Charles Pinckney was building a mansion house at Colleton Square, between today’s Market and Guignard streets. He and his wife, Eliza Lucas, went to Europe in 1753, and for years their impressive brick house was rented for South Carolina’s governors. James Glen (governor 1743-1756) was the first to have his official residence in the Pinckney mansion; Lord Charles Greville Montagu (governor 1776-1773) was the last.

Over the years, the bridge that led to the governor’s lodging became known as Governors Bridge. Charles Fraser, born in 1782, remembered the bridge as “a wide brick arch thrown across a creek, into which the tide flowed, from where the fish market now stands nearly up to Meeting Street, and covering almost the whole extent of our present market.”

Waterfront Development

Below Governor’s Bridge, Daniel’s Creek was not filled in for many years, but Craven’s Bastion, the northeast point of the ring of defenses built around Charleston in the early eighteenth century, disappeared beneath made land and new construction. After the establishment of the market between Meeting and East Bay streets, in 1807 the Commissioners of the Centre Market built a new fish market east of the Governor’s Bridge. Although the creek had been significantly narrowed, there was still enough tidal flow in “Market Street” to constantly refresh the fish market basins.

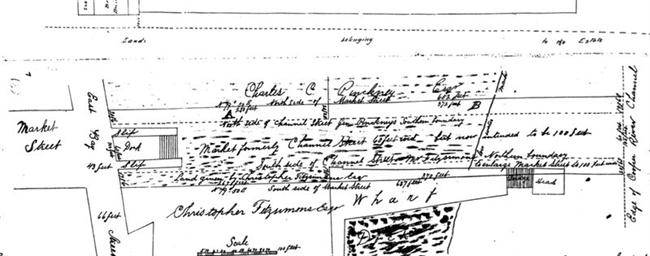

South of the creek was Fitzsimmons Wharf, whose loyal patrons included the operators of several steam packet boat lines. The wharf was part of the area purchased by the federal government in 1849 for construction of a new United States Custom House and dock.

Bates, Susan Baldwin, and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds. Proprietary Records of South Carolina. Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of The Province, Charles Towne, 1678-1698. Charleston: History Press, 2007.

City of Charleston Engineer’s Plat Book. Index book and microfilm, S. C. History Room, Charleston County Public Library.

Fraser, Charles. Reminiscences of Charleston. Charleston, 1854. http://books.google.com

Mayrant, Drayton [Katherine Drayton Mayrant Simons]. “Charleston Wharves, 1866,” in Claude Henry Neuffer, ed. Names in South Carolina. Vol. 14. University of South Carolina, Winter 1967.

Smith, Alice R. Huger, and D. E. Huger Smith. The Dwelling Houses of Charleston. J. B. Lippincott Co., 1917. http://books.google.com

WmSeabrook24Oct1831Patriot_650x650.jpg)

MarketHall_650x650.jpg)

CustomHouseEngraving_650x650.jpg)