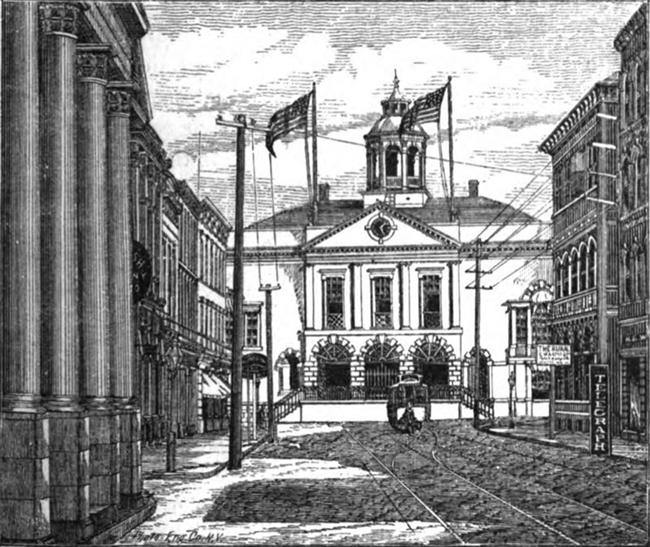

17. Watch House (1719-1767) Exchange (1769) Council Chambers (1735)

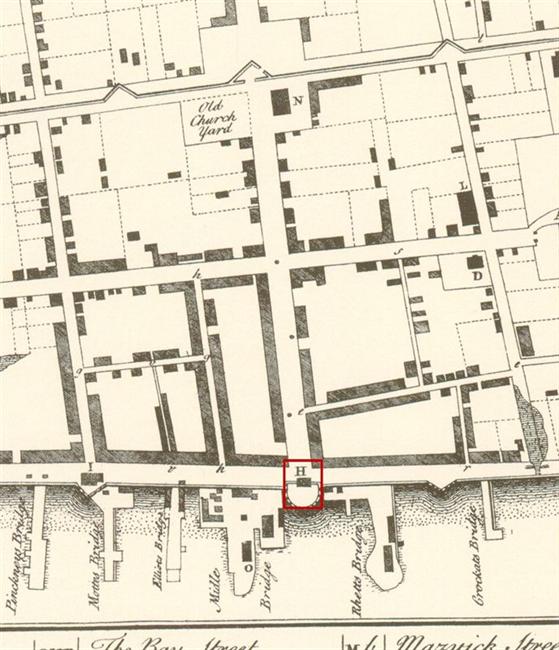

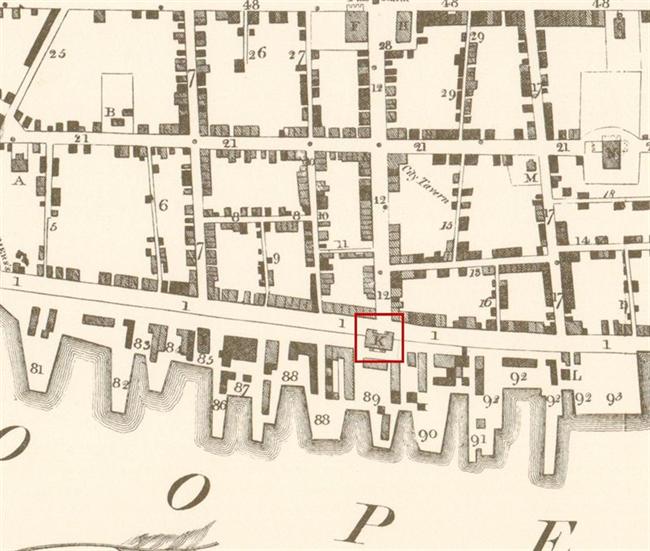

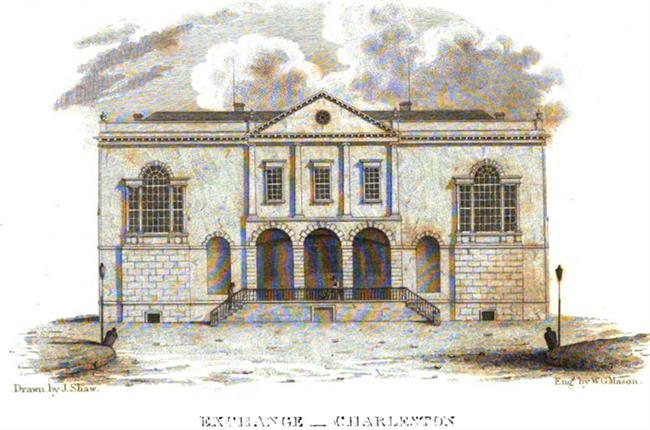

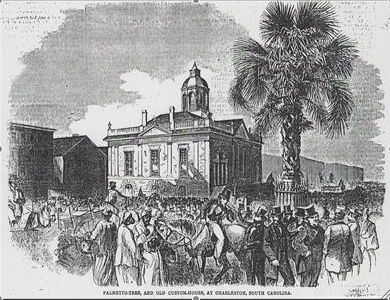

The Exchange Building stands beside the Cooper River at the foot of Broad Street, a location that has been continuously used for public functions. Here, at the midpoint of Charleston's fortification wall, the Half Moon Battery projected into the river. Completed after 1701, this large semicircular structure not only strengthened the harbor's defenses, but also served as the formal entrance to the city. By 1711, a two-story building stood atop the Half Moon Battery. On the ground floor was the Guard House; at the upper level was the Council Chamber. As one of the largest indoor spaces in colonial Charleston, the Council Chamber accommodated social gatherings and concerts as well as meetings of the governing body it was designed for, the Grand Council. Comprising the governor and other deputies appointed by the Lords Proprietors, the council was established to govern South Carolina in accord with the proprietors' interests. A separate elected body, the Commons House of Assembly, was authorized in 1692; both were retained when South Carolina became a royal colony. Beginning in 1753, both the council and the assembly met in the State House erected at the northwest corner of Meeting and Broad streets (today's Charleston County Courthouse). Charleston was a commercial center, one of colonial America's principal seaports. In 1767 the Commons House of Assembly granted £60,000 to build a waterfront Exchange and Custom House above the Half Moon Battery, also funding a replacement for the Guard House. A new Watch House would be built at the corner of Meeting and Broad streets before the new Exchange Building was constructed. The new Exchange and Custom House would provide for several complementary activities: it was needed "for the assembling and meeting of persons concerned in promoting trade and commerce, for the keeping the offices of the collector of his Majesty's customs, and the naval office, and for the meeting of the inhabitants of the town and Province." A design by architect William Rigby Naylor was selected, and masons Peter and John Horlbeck were contracted to construct the building. Two full floors above a substantial basement, it provided an open ground floor for the exchange (a commercial and financial trading market that was a precursor to modern stock exchanges) and a large assembly room and offices for customs officials at the upper level. With much of the stone and slate being imported from Great Britain (sixty tons of stone landed in November 1769), the building was not completed until 1771. It remains one of the finest examples of early American civic architecture. Portions of the Half Moon Battery remain in the basement of the Exchange. Although the fortification was dismantled, its underground brick construction was reworked as fireproof storage cellars available for rent or for public use. English tea seized after the Tea Act of 1773 was stored in these cellars; during the Siege of Charleston in 1780, General William Moultrie removed 100,000 pounds of gunpowder from the Old Powder Magazine to the Exchange building. When the British occupied the city, they turned the secure cellars beneath the Exchange into prison cells. On August 4, 1781, Colonel Isaac Hayne was taken to his execution from a cell in the Exchange Building. When the City of Charleston was incorporated, the Exchange and Custom House became City Hall. The 1788 convention at which South Carolina ratified the United States Constitution was held in the upstairs assembly room, which was also the frequent location of private concerts and dances. The Exchange Building was the center of President George Washington's public activities during his visit to Charleston in 1791. On May 3, he sat beneath “a beautiful triumphal arch” for dinner with the leading citizens. Afterward fifteen toasts and speeches were accompanied by cannonshots. The next night, Washington went to a "dancing Assembly at the Exchange," and again on May 5, the Exchange was decorated for a concert "at which there were at least 400 ladies—the number & appearances of which exceeded any thing of the kind I had ever seen." In 1818, the City of Charleston deeded the Exchange and Custom House to the federal government, and received title to the Bank of the United States property at the northeast corner of Broad and Meeting streets. City Hall was relocated to the bank building, and the Exchange building was remodeled as Charleston's main post office and customs offices. After the Civil War, the federal government renovated the building, with construction work carried out by local contractor/ architect Christopher Trumbo. The Customs Service moved to the new United States Custom House at 200 East Bay Street in 1879, and in 1897 a new post office opened the southwest corner of Broad and Meeting streets (site of the 1767 Watch House). Turned over to the United States Light House Service in 1898, the old Exchange and Custom House served various federal agencies until after World War One. Following congressional authorization in 1913, the United States government deeded the Exchange and Custom House to the South Carolina State Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The Rebecca Motte Chapter of the DAR has made its headquarters in the building since 1921, renting some of he offices to federal agencies until 1950. While the Daughters of the American Revolution still hold title to the Exchange and Custom House, since 1976 the Old Exchange Building Commission, a state agency, has administered the building through a series of long-term leases. In 1998, the City of Charleston accepted responsibility for management of the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon as an historic site. The Exchange Building has been repaired and altered in several significant renovations. About 1800, two stair towers at the outer bays of the west façade, which extended about fifteen feet into East Bay Street, were removed and replaced by a large interior stair. The original cupola was lost before 1817, and a new cupola placed on the roof in about 1835. Some of the ground floor arcades were infilled in the 1830s; the remaining openings were infilled after the Civil War. By 1883, the second cupola had deteriorated and was removed from the roof; the original stone parapet, topped by urns at both facades, were toppled in the earthquake of 1886. The renovation that began in 1979 was designed by the local architectural firm of Simons, Mitchell, Small and Donahue, and completed by Charleston Constructors. Two stair towers were added to the east façade, originally the building's more important elevation, while the roof level was restored with a parapet and cupola. In 2004, ongoing problems with water penetration around the window and door openings led to a thorough repair of the exterior masonry and stucco by contractors Stier, Kent and Canady, Inc., working with Liollio Associates, architects. United States Custom House, 200 East Bay Street The original Exchange and Custom House was much too small for the many bureaucrats required to handle the commercial traffic in nineteenth century Charleston Harbor. In 1850, Ammi Burnham Young, architect for the United States Treasury Department was appointed to develop a design based on four of the entries in an architectural competition held the previous year. The final design incorporated a colonnade proposed by Charleston architect E. B. White, who worked as superintending architect for the project from 1851-1860. The granite and marble building rests on a foundation supported by 7,000 piles driven into the reclaimed marshland south of the City Market. Much of the Custom House had been finished when the Civil War began, and work resumed in 1867, but the building was not finally completed until 1879. Butler, Nic. "Rediscovering Charleston's Colonial Fortifications. A Weblog for the Mayor's Walled City Task Force." http://walledcitytaskforce.org Behre, Robert. "Landmark Project. Repair work on Old Exchange Building grows in scope." Post and Courier, July 25, 2004.

|

Exchange1711_650x650.jpg)