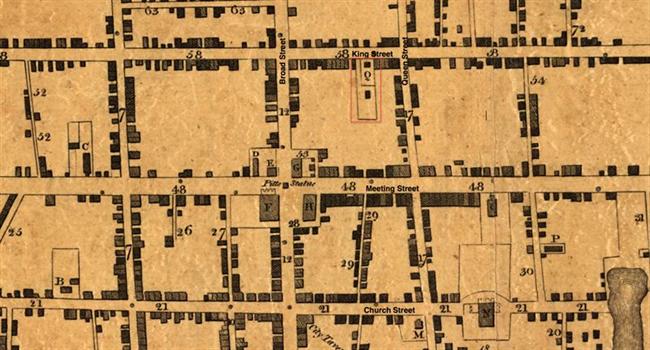

21. Quaker Meeting House

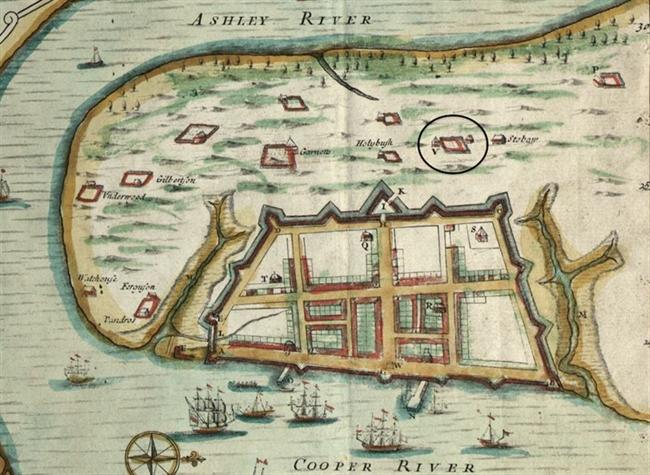

Among South Carolina’s earliest English colonists were a few Quakers, members of the Society of Friends. They established a burying ground on Archdale Square, and in 1696 Thomas Bolton left £10 in his will for repairing the fence of the plot and building “a little house” for meetings. Complete records of property transactions within Archdale Square have not been found. The “Quaker Lot” was warranted to Mr. Thomas Kimberly in 1717, and granted to him in 1731. Kimberly, in turn, conveyed the lot to trustees for building a meeting house. In 1754 the Friends resolved to repair the meeting house, which was “very decayed.” The building was again neglected as Charleston’s Quaker population dwindled during the second half of the eighteenth century. In 1812 the small congregation deeded the property to the Society of Friends in Philadelphia. The Quaker Meeting House, a simple frame building with a slated roof, was blown up by firemen in order to stop the southward path of the Queen Street fire of July 1837. The Charleston Mercury and Daily Courier reported the loss with similar phrases: the “Quaker meeting house, which has so long lifted its little head among us;” a “small and plain building that for many years exhibited … the meek and humble character of the sect to whom it belonged.” The meeting house was not replaced after the fire. In 1856, the Society of Friends in Philadelphia retained Charleston building contractor Mr. Busey to erect a brick meeting house fronting twenty-five feet on King Street. There was no one to use the building; its purpose was to prevent the property from escheating (reverting) to the state as a vacant parcel with non-resident owners. The new meeting house was destroyed by the great fire of December 1861, and never rebuilt. In 1968, Charleston County bought the lot, known as the Quaker Burial Ground, from the Society of Friends in Philadelphia. The Friends concurred with the county’s plan to use the site for a parking garage, with provisions for relocating the burials. Although there were only three gravestones, many more burials were found during the two-stage construction of the garage. Some of the remains were relocated within the site; most were removed to Courthouse Square, the greenspace beside the O. T. Wallace County Office Building on Meeting Street. Bates, Susan Baldwin, and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds. Proprietary Records of South Carolina. Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of The Province, Charles Towne, 1678-1698. Charleston: History Press, 2007. “Crews Finish Relocating Quaker Cemetery Graves.” News and Courier, February 1, 1969.

|